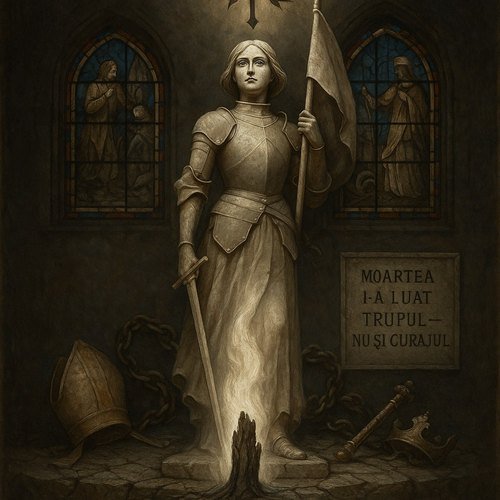

May 30, 1431: Joan of Arc — Trial by Fire, Judgment by Hypocrisy

On May 30, 1431, Joan of Arc—peasant girl, warrior, and heretic—was burned alive in Rouen at the age of 19. In the brutal chaos of the Hundred Years’ War, she rose from obscurity to lead armies and crown a king—only to be betrayed by both Church and Crown. This unflinching historical deep dive exposes how those same institutions that condemned her to death (as a heretic) would, centuries later, sanctify her memory and raise monuments in her name. It’s a raw exploration of power, fear, manipulation, and the cost of defying systems that demand obedience—and punish truth. Joan was not just sacrificed; she was recycled by history.

Joan of Arc: Fire, Crown, and Hypocrisy

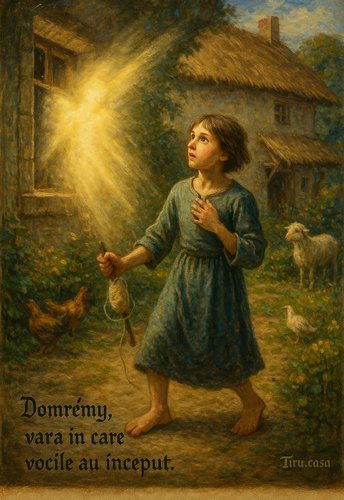

The Maid of Domrémy

In a humble village under the great belfry of Lorraine, a bright-eyed peasant girl named Jeanne d’Arc grew up among animals and wheat fields. She was small of stature but ferocious in spirit – by age thirteen she was sewing and spinning like any farm girl, though “in sewing and spinning I fear no woman in Rouen,” she later boasted. One summer day, as sunlight filtered through the kitchen window, she froze in shock. Before her stood a brilliant angelic figure. “I was thirteen when I had a Voice from God for my help and guidance,” Joan later testified. The vision came “mid-day, in the summer, in my father’s garden,” accompanied by a “great light” that seemed to issue from the angel’s lips. She “believe[d] it was sent… from God”. This summons demanded she abandon the quiet weaving of hearth and home for a grand purpose: to save France.

Just a few years later, an unwed country girl with clipped hair and a wart on her chin would stand before kings and armies. But first Joan began quietly – a solitary figure reciting prayers beneath the Ladies’ Tree in Domrémy, learning that personal faith could clash hilariously with rigid tradition. At home she was obedient; among the voices and visions she became all grit and fire. Even as a child, Joan had a fiery wit: when villagers gossiped about saints, she quipped that her own saints were “better company than any maid at the alehouse.” In her tiny church, she whispered “Deus, in adjutorium meum” (“O God, make speed to save me!”) and imagined saintly answers. She ran errands as fast as cavalry, but her imagination ran faster.

Visions in the Garden

By May of 1425, Joan’s peasant life was fading behind a new destiny. She rode horses across countryside, but not on errands for her family – on messages from beyond. The voices of saints Catherine, Margaret, and Michael became her constant companions. She described them: the saints seemed real, with “jeweled crowns” on their heads, and they spoke to her in comforting tones. Asked who sent these messages, Joan would boldly answer that the King of Heaven himself was behind them: “God and the Church are one,” she said when quizzed, bewildering her French inquisitors.

No ordinary child would dare such words. Yet Joan insisted it was not fantasy but mission. When critics mocked her male battle-harness and cropped hair, she laughed that “the clothes are a small matter, the least of all things”. They hurled the cruelest accusation – cross-dressing, an “abomination,” they said, that damned the soul. She replied with the same fiery logic: if God himself told her to wear men’s garb for her safety, she’d rather die than cast it aside. In truth, the only sin she admitted was saying no to God. When asked if she would obey the Church, she answered without irony that she always did – after all, she believed, “God and the Church are one and the same, and there should be no difficulty about that”. In other words, God told Joan her heart was pure.

Her visions felt as concrete to Joan as morning sun. “I saw them with my bodily eyes, just as well as I see you,” she later said of Saint Michael and the others. This vivid reality left her determined beyond fear. At times, she even bore her banner instead of a sword, hoping “to avoid killing anyone myself” – fierce, but merciful too. In the rolling fields of France, Joan found a surprising kinship with farmers and shepherds; she saw that her voice for France’s liberation echoed theirs. The year she was 16, Joan slipped away secretly to chinon to seek an audience with the Dauphin (the uncrowned Charles VII). On the way, she described to her escort how the Burgundians’ recent cruelties had turned Christian fields into charnel houses. She warned in poetic old words, “Notez que Dieu, qui aux tors faiz repune, ceulx relève en qui espoir maint” – “Notice how God, who punishes wrongdoing, raises up those in whom hope remains”. The idea startled the ferryman: these were the words of Christine de Pizan’s famous poem, an educated letter under the peasant’s mouth. A vision anointed by literature, as if both heaven and the voice of Renaissance reason spoke through her.

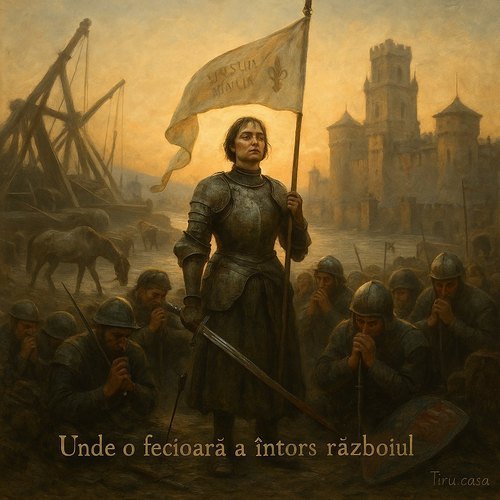

The Siege of Orléans: Steel and Faith

Dressed in practical soldier’s attire, Joan marched behind Vaucouleurs and Chinon, beside newly printed cannons and helmeted men-at-arms. She was still a teenager carrying the weight of a nation’s hopes – a weird guardian watching over scarred soldiers and frightened villagers alike. Medieval France was a land at war, where a girl’s single sword was as heavy as a sun. Yet Joan took it up willingly, recalling the fields of wheat and anger under which her voice had sung. Against grumbling skeptics she insisted God’s light guided her strategies. Soldiers grumbled when she set campfires or surprise assaults, but they also whispered astonished thanks that the Loire and silence yielded to their cause.

In April 1429, a week after she arrived at Orléans, the English garrison lifted the siege. This was no mere battlefield acclamation: it was a reversal of fortune worthy of legend. Those who had almost starved now danced at Joan’s feet, beating drums and church bells in praise. Christine de Pizan noted this as a miracle: “Did anyone… see anything so extraordinary come to pass?… It is a fact well worth remembering that… God… bestowed such great blessings on France through a young virgin”. Indeed it was. Joan, once silenced by society, now spoke for all: the blind, the motherless, the thrice-trampled peasant. She thought of them as she pushed Charles to Reims.

No crown was safer with her than the muskets of war. She was wounded by an arrow at the siege of Les Tourelles, and yet let it be known she told the Dauphin beforehand: “I knew I would be wounded”. The shock of the arrow sent her to her knees once more – not in pain, but quietly stating the prophecy had been true. Each battle felt like dicing with Death, but each victory felt like Heaven’s handshake. Meanwhile, England’s courts fumed. Hearing this peasant-maiden could rally France stung them more than losing a castle. And so soon the war shifted.

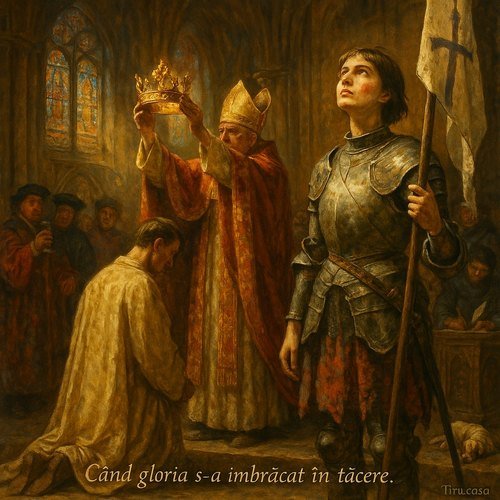

A Crown of Lilies and Doubt

By summer 1429 Joan guided Charles to Rheims, under skies smelling of honey and grief. The cathedral’s walls echoed with “Hosanna!” from the loyal nobles who once sneered at France’s heir. In this hallowed place, a simple banner transformed into divine script. When the holy oil poured on Charles’s head, Joan felt vindicated: France was saved because she had dared to speak for God. Yet the curtain of triumph also hid a royal hypocrisy. For Charles VII, this war was a political drama, and Joan was suddenly an inconvenient actress.

The king’s cheers were warm, but his gratitude was cooler. In Toulouse, at a feast she expected the king to unclasp her heavy breastplate, his courtiers mockingly accused her of romanticizing war. Joan retorted with humor: “Je souhaite mieux: moi je l’aime bien le roi quand il porte un chien autour du cou!” – “I wish it for the best: I very much like the King when he wears a dog around his neck!” (a reference to a hairy hound that Charles fed during the coronation). The jest wasn’t in the trial transcripts, but it fits the rough, gallows humor she often used to cut through pomp. For the King, though, her wit was as unwanted as a peasant at court. He had used her as a holy banner to win battles, and now feared her political star might eclipse his throne. So he kept silent as allies plotted.

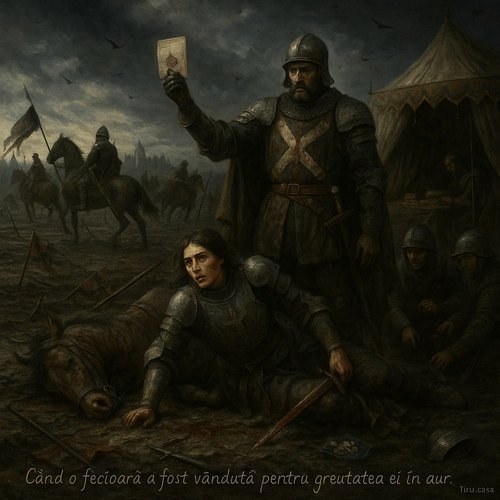

The Traitor’s Noose at Compiègne

Winter turned to spring of 1430, and Joan found herself far from crowns in Rheims. In icy Compiègne, press gangs of mercenaries closed in. One Burgundian captain blocked her escape route. “You cannot pass!” he snarled, then showed a letter from the Duke of Burgundy. Her escorts scattered, leaving Joan cornered like a rabbit in a thicket. She rode through a hail of arrows and bloodied her side in a desperate charge – a final soldier’s boast. But a crossbow bolt felled her horse.

Dragged to Burgundy’s rear guard, Joan faced the grotesque sight of a traitor’s sale. In a perfumed tent, the proud Maid was sold for ten thousand golden pounds – a king’s ransom – to the English. By July of 1430, she was in Rouen, bound by iron and doubt. Even her judges, the very Churchmen who would condemn her, showed respect. They offered a reluctant sacrament before the flames, as if salvation could wash away their crime of murder.

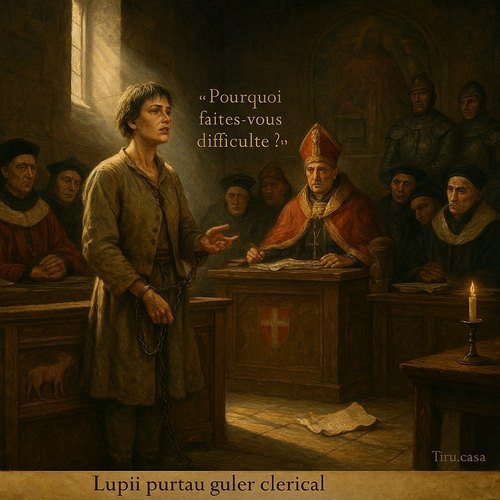

The Rouen Tribunal: A Farce of Justice

Joan’s prison in Rouen was a cage gilded with learning. Before a makeshift court of dubious clerks and English soldiers, she stood trial for her “errors” – the same acts that France once celebrated. The long transcripts read like a caricature of justice. She was asked once more about her voices and the “magical angels”; Joan sternly answered that only God commanded them. When they demanded proof that her visions were not the Devil’s work, she made them blush: she swore God and His Church were not enemies, and thundered “Pourquoi faites-vous difficulté?” – “Why make such difficulty about it?”, exposing their own contradictions.

Most absurd was the final charge: cross-dressing. Cauchon’s tribunal pretended this simple act of practicality was heresy. The clothes were “men’s,” they sniffed. Joan, pious and stubborn, replied that her skin and soul were surely more important than thread. “The clothes are a small matter,” she said defiantly. That remark, apparently so trivial, was twisted into a capital crime. After forcing Joan to renounce her mission under duress – she even signed a statement abjuring her voices and vowing to wear women’s dress – the tribunal then turned on its heels. Joan let down her prison gown and put on the soldier’s doublet again. Immediately, they proclaimed her a “relapsed” heretic.

The hypocrisy couldn’t be thicker. The Church – which once rode proudly to war herself – donned English colors to break its own heroine. The King – who owed his crown to this Maid – pretended she didn’t exist now. Even so, Joan faced it all without flinching. In that courtroom, she was like a lamb among wolves, but these wolves wore robes and clerical collars. France and the Church used her for miracles; now they burned her as a witch.

“But, three days later in prison, Jeanne again wore men’s clothes… and the tribunal immediately condemned her for lapsed heresy on the grounds of cross-dressing”

Flames on the Hill

The morning of May 30, 1431, was cold and gray. Joan of Arc – now Jeanne la Pucelle – climbed the scaffold at the Old Market in Rouen. Around her neck she bore a large wooden cross, a sinner’s brand meant to mock her. She planted her feet on the platform, nailed as firm as Christ’s own stake. When they asked if she accepted this sentence, she stood tall: “If I have not spoken truly, may God put me there; and if I have, may God keep me in it… May Jesus have mercy on me” (her last words, according to witnesses). The fire was lit.

As smoke curled around her, Joan prayed: a chorus of “Jésus, Jésus!” rose from her lips, merciful and brave. Her soldiers and countrymen watched silently – the triumphant banner of France had turned to ash. If any physical martyrdom can have dignity, hers did: only the inquisitors wore evil grins as the flames claimed their champion. The crowd saw a pale teenage face, tear-streaked but unrepentant, staring through the flames at some distant cathedral of the mind. She might have believed the fire itself was baptism by Heaven. Nearby, the church bells fell silent, not for justice, but in mourning.

In retrospect, this brutal irony was soon echoed by history. Within twenty-five years, King Charles VII – who had done nothing to save her – ordered a Church commission to re-open the case. The outcome was buried in textbooks of law, but clear: the 1431 trial was a sham. An ecclesiastical court ruled that “the judgement of the original trial was not valid because it was biased and had not followed proper procedure.”. The Church formally exonerated Joan as an innocent victim of politics. Only two Catholic popes later (489 years after her death!) would officially canonize her. By then, any pretense of infallibility was laughable.

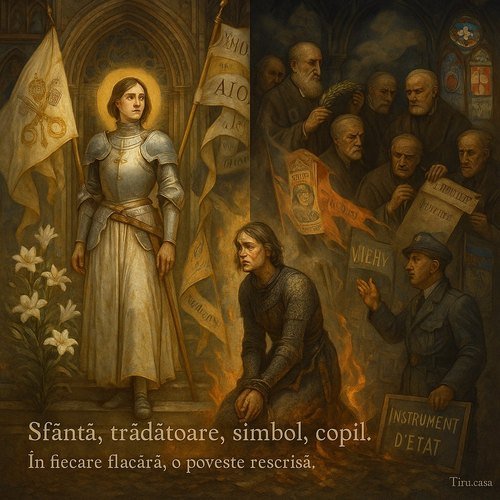

The Crown’s Pawn and the Church’s Saint

Over the centuries, Joan’s legacy split like light through a prism. Some saw a rebel soul, betrayed by kings and bought by Englishmen; others saw a saint, raised on high by the very Church that burned her. Truth was, both were right. In the late 19th century, France’s elites dusted off her story as France lost territory to Germany, calling her “the daughter of Lorraine… patron saint of the invaded” and a symbol of French unity. To conservatives she was an unshakable saint who defended kings; to socialists and radicals she was a young heroine “burned by the Church and abandoned by the king”. Even during World War II both collaborationist Vichy and Free France claimed her – one as a crusader against occupiers, the other as a freedom fighter.

Despite the mythic status, Joan’s memory exposed hypocrisy at every turn. The Church took fifteen minutes to burn her at the stake, and nearly five centuries to clear her name. Then it canonized her during a bitter secular-versus-church fight, turning this “peasant rebel” into a weapon in Vatican diplomacy. Kings who never lifted a finger to help were glad she got Holy Ribbons decades later. England, too, eventually erected memorials out of guilt. Yet the Maid herself was never religious for political gain – she mocked opulence and never claimed sainthood.

Today, in modern language, Joan’s story is a case study in institutional manipulation. She had entered history as a tool of monarchy and later became a pawn of Church politics. In textbook French, she’s an “instrument d’État” – an instrument of the State. Protestant writers even began praising her as a proto-Protestant martyr (though France’s king was always Catholic). The reality is darker: she was thrown away as soon as she’d done her duty and only reborn when her legend suited powerful agendas.

But beyond politics, Joan of Arc remains a portrait of youthful courage crushed by hypocrisy. At nineteen, she bore more horrors than most see in a lifetime. Imagine that burden: a child plucked from sunlight and flung into cannon smoke. UNICEF today notes that thousands of children are dragged into modern wars – soldiers with smaller rifles, less magical visions, but just as few choices. Joan’s voice can be heard in theirs when armies play dress-up with doctrine. She shouldered a nation’s weight onto teenage shoulders, a burden both gallant and grotesque.

May 30th Through the Ages: Fires, Flags, and Forgiveness

Ironically, Joan’s death-date, May 30, has become a canvas for other histories. On May 30, 1868, Americans held the very first Decoration Day – later renamed Memorial Day – to honor soldiers fallen in the Civil War. In a strange symmetry, that national day of mourning falls on the anniversary of France’s teenage martyr. On May 30, 1845, indentured Indians aboard the Fatel Razack arrived in Trinidad, forced into colonial fields – a migration of poor souls not unlike how Joan’s war pressed ragged peasants into service. In Puerto Rico, May 30 is Lod Massacre Remembrance Day, commemorating the 1972 attack on innocents – another brutal reminder of fanatic violence made the text of living victims, just as Joan was turned into martyrs’ ash. On May 30, 1967, the tiny island of Anguilla expelled its colonial overseers and declared self-rule, echoing Joan’s defiance against foreign domination.

Across centuries, therefore, May 30th has seen both tyranny and tenacity: battles lost and hard-won independence; blood and memory. Each event is an allegory: Joan died a pawn, but lives in legend; Anguillians fought as pawns, yet carved freedom from rulers; the Fatel Razack passengers were pawns of empire, yet now honored as forerunners of a new nation; the Martyrs of Lod were victims of twisted cause, as was our Maid; and in America, the fallen of every war are collectively mourned. In all these, power and propaganda meet sacrifice. Joan’s voice, once drowned by flames, still speaks through them all – reminding us that “even in darkness our hope remains” (as Christine de Pizan wrote).

Legacy and Lessons

Today Joan of Arc is sculpture, story, and liturgy. She is a patron of soldiers and a symbol of women’s courage. Yet beyond monuments and National Holidays, her tale warns: institutions that worship power can vilify the very people who save them. A rural girl with no title showed kings how to be brave, and the same royal hall disposed her with barely a sigh. The Church that canonized her in the 20th century condemned her in the 15th.

In the end, Joan’s irony is eternal. A cross pressed to her bare neck became a saint’s crown in stone. The fires that consumed her still kindle ideas: of truth, exploitation, and resistance. If people today invoke Joan for any cause, let it be in memory of a truth she embodied: * “You may burn my body but never my faith,” * she once said – an act of faith that even in martyrdom, became her victory.

Analogies and Echoes on May 30

- 1868, USA: The very first Memorial Day (Decoration Day) was observed May 30 – a somber tribute to war dead that, like Joan’s execution day, honors sacrifice.

- 1845, Trinidad & Tobago: The ship Fatel Razack landed indentured Indians on May 30. These laborers were pawns in an empire’s economy, much as Joan became a pawn in France’s power struggles.

- 1967, Anguilla: Islanders expelled colonial troops on Anguilla Day (May 30). Their small rebellion against empire echoes Joan’s own revolt against foreign invaders.

- 2007, Puerto Rico: May 30 was declared “Lod Massacre Remembrance Day” to honor victims of terrorism – a modern tragedy from fanatic zeal, paralleling the senseless violence of Joan’s execution.

Each of these dates carries Joan’s legacy of sacrifice vs. propaganda into our age: children in war, exploited masses, and nationalist myths. Joan’s life and death remain alive in all these, a reminder that the struggle against hypocrisy and oppression spans ages.

Citations:

- The Trial of Joan of Arc: An Account

- Transcripts & materials on Joan of Arc’s voices and trial. Indiana University

- Clothing | Joan of Arc | Jeanne-darc.info

- Trial of Joan of Arc

- Christine de Pizan, Le Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc

- 100 Years After Canonization, Joan of Arc Remains a Symbol for Many

- Children Recruited by Armed Forces

- History of Anguilla – Recent History

- May 30 – Historical Events

- Lod Airport Massacre – Remembrance Day

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0