🪨 12 May 113 CE – The Day Rome Immortalized Its Empire in Spirals of Stone

Discover the story behind Trajan's Column, one of the greatest achievements of the Roman Empire. On May 12th, 113 CE, Rome celebrated a monumental victory, and through this column, engraved its eternal history in stone. Learn how this monument deepens our understanding of the Roman world and an empire that once ruled the ancient world.

Echoes in Stone: Decoding the Legacy of Trajan’s Column

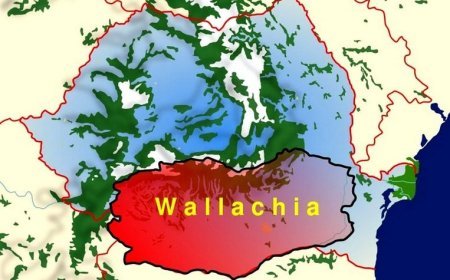

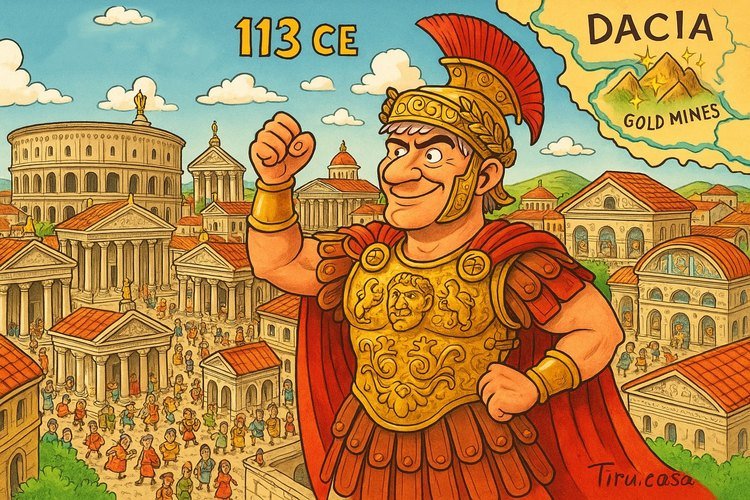

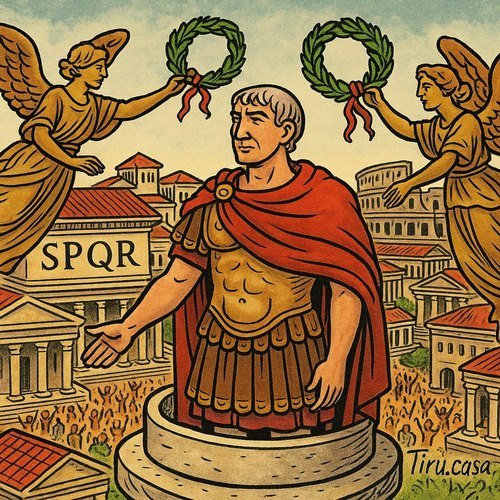

It was inauguration day, May 12, 113 CE (think nearly 2000 years ago!) – and Emperor Trajan was the star of a gigantic new monument in Rome. This wasn’t just any old statue; it was a soaring 39-meter spiral column covered in carved scenes of his victorious wars in Dacia (modern Romania). Over two exciting campaigns (101–102 and 105–106 CE), Trajan had beaten the Dacian king Decebalus and looted Dacia’s gold, and now he wanted everyone to remember it. Think of the Column as ancient Rome’s version of a blockbuster movie poster – or a really long comic strip winding up into the sky.

Trajan’s Column tells a story about war, wonder, and political pizzazz. But why carve a moving story into marble instead of, say, writing a history book? Well, for Romans this was propaganda with style: a way to brag about the victory and record it for posterity. The Senate and People of Rome even wrote a modest-sounding inscription on the base – SPQR (“Senate and People of Rome”) to Emperor Trajan – which basically says it was made “to show how great a height [this] mountain and [this] site had been raised by such great works”. (In other words: “Wow, look how high and grand we built this thing!”).

Chapter 1: Rome’s Big Idea in a Little Wax Tablet

The World in 113 CE

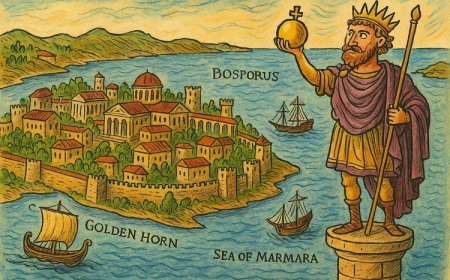

Imagine ancient Rome as a huge, mega-busy city at the heart of an empire. Emperors built grand temples, forums (marketplaces), baths, and monuments. Trajan (ruled 98–117 CE) was one of the most popular emperors – a bit like your favorite superhero ruler. He was born far from Rome (in Hispania, modern Spain) and had served bravely as a general. Under him, the empire stretched out further than ever before, especially after conquering Dacia.

- Roman Pride: Trajan was famed for being good to his soldiers and tough on enemies. The Senate loved having him; they even carved all his full titles on monuments. (His titles included “Germanicus” after defeating Germans and “Dacicus” after defeating Dacia.)

- Why Dacia? The Dacians (north of the Danube River in today’s Romania) had gold mines and troubled Rome’s borders. They’d beaten a Roman army in the past. Trajan needed resources and glory, so Dacia was on his list. Some historians think he attacked Dacia to prove himself as an emperor (since he was adopted by Nerva and wanted to show he was a great leader), and others say he was lured by Dacia’s gold to fund big building projects in Rome. Probably both!

Chapter 2: Meet Emperor Trajan and King Decebalus

The Emperor and the “Barbarian” King

Trajan – born Marcus Ulpius Traianus – was like Rome’s rock star: tall, strong, always fair. He loved sports, building things (he built roads, bridges, and markets), and winning battles. Romans even called him “Optimus Princeps” (the Best Ruler). He was officially adopted by Emperor Nerva in 97 CE, making him Caesar and then Emperor when Nerva died. By 101, Trajan turned his attention to the north.

Decebalus – the Dacian king – was clever and tough. (Dacians sometimes called him by other names like Diurpaneus.) Unlike Rome, Dacia had no big cities or senates; they had tribes ruled by fierce kings. Decebalus had previously negotiated with Rome (even taking huge bribes under Domitian), but Trajan suspected him of hiding forts and weapons. He bristled at giving up territory. So, civil discussion was out; war was on!

Political and Cultural Clash

- For Rome: Conquering Dacia meant more land, gold, silver, and tribute. They got a massive new province and bragging rights. It literally paid off: contemporary writers bragged about the treasure hoards (some say 500,000 pounds of gold!) hauled back to Rome.

- For Dacia: Loss meant the end of their kingdom and freedom. Dacia was famous to Romans for its warriors (think “Wolf Warriors” – Dacians used a wolf-dragon banner called the draco). To Dacians, the column in Rome might have felt like a monster trophy in enemy territory. But for the column-makers, it was a proud display of Roman strength.

Chapter 3: The First Dacian War (101–102 CE) – Training Camp Chaos

The Spark and the Siege

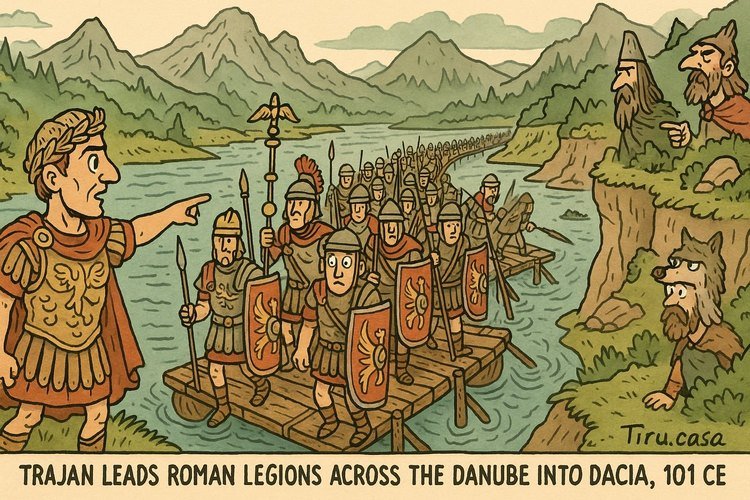

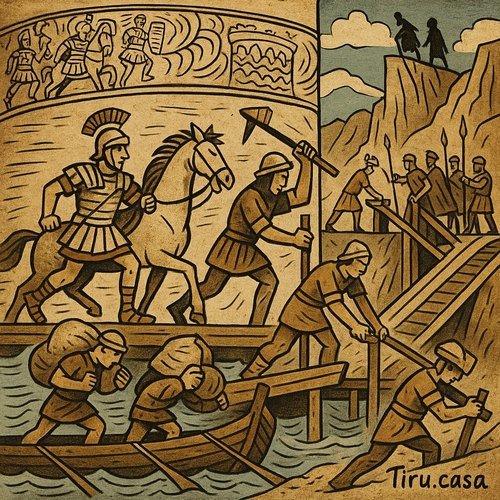

In 101 CE, the Roman Empire was like a horde of calm cats – and Trajan was the catnip! He launched the First Dacian War because Decebalus was fortifying his borders and even besieging Roman forts across the Danube. Trajan crossed the river (on shaky boats or a wooden bridge he built) into wild Dacian territory with tens of thousands of legionaries.

Roman writers tell of several key battles in the forests and mountains of Dacia. One famous fight was at Tapae Pass (a narrow valley): Dacians, on horseback wearing scary wolf caps, charged the Romans. The fighting was brutal, with arrows and swords flashing.

In the end, Trajan’s discipline won. After some pitched battles, Decebalus sent envoys to the Roman Senate (they even laid down their weapons in supplication) to sue for peace. Seeing this, Rome granted a “peace” in 102 CE: Dacia had to surrender territory and demolish some forts.

The Aftermath – Twists and Treaty

Though it looked like a Roman win, the treaty terms were pretty lenient to Decebalus. In fact, Trajan might have thought “Hmm, did we go easy on him?” – and maybe Dacia did, too. Decebalus kept some defenses, and Rome even paid him subsidies (money) to keep the peace… which he used to rebuild his strength. Historians think Trajan suspected this and started preparing for round two.

Bullet Points:

- What Worked for Rome: Discipline (legionnaires fought in tight formations) and tactics (Romans built forts every night, made stakes in rivers to block cavalry, etc.). They also had engineers who made a 19.3-kilometer road along the Iron Gates of the Danube cliffs!

- What Went Wrong: Overconfidence? Romans were ambushed at Tapae once and took heavy losses. The terrain favored the Dacians (forests, mountains). Also, surprise plot: Decebalus tried to hire foreign mercenaries (including a Moorish deserter) to kill Trajan in camp. Thanks to Roman guards, the plot was discovered and foiled. Imagine the camps on edge, wondering if anyone wearing a Moor’s skin is actually a secret assassin!

Chapter 4: The Second Dacian War (105–106 CE) – Game Over for Dacia

When Peace Broke (Again!)

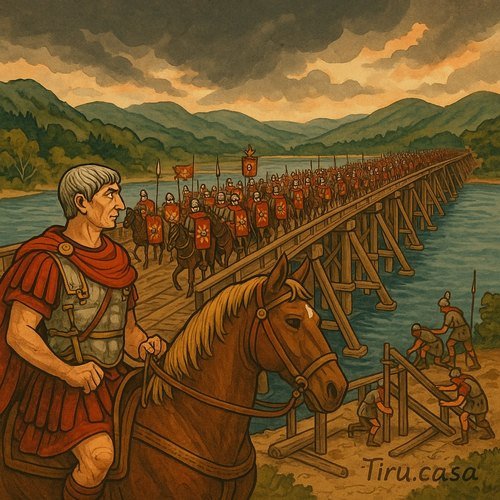

By 105 CE, Decebalus was back to old tricks: rebuilding forts, rearming, and breaking the treaty. The Roman Senate declared Dacia enemy again, so Trajan had no choice but to march north once more. But this time, he meant business: complete conquest.

Trajan planned a two-pronged attack. One of the coolest stories is that he ordered Apollodorus (his chief engineer) to build an enormous wooden bridge over the Danube – a 400 meters (2,200 feet!) long – in just a few months! This allowed Roman troops and horses to walk straight into Dacia without delay. (Imagine a line of legionnaires marching “over the river” on a giant floating log path – it’s like ancient engineering met Mario Kart.)

The Big Siege and the Escape

The climax was the siege of Sarmizegetusa, the Dacian capital hidden in the Transylvanian mountains. Romans surrounded it and cut off supplies. There were scenes of furious fighting: Roman slingers and bowmen against Dacian cliffs, wolves howling somewhere, dirt flying.

In one famous panel (and in history), King Decebalus tried a sneak escape. According to legend, he hid in a hollow metal cuirass to slip out of the city, but a loyal freedman caught up with him and killed him (some say Decebalus took poison instead). Either way, the Dacian war effectively ended when their king was gone and their capital fell.

Roman sources (and even surviving carved scenes) show Roman victory on a grand scale. Cassius Dio notes that before the final stand, Decebalus again asked to surrender territory – still hoping for mercy – but Trajan refused to give back anything. There would be no more peace treaties; Dacia was now Rome’s new province.

Chapter 5: Designing and Raising the Column

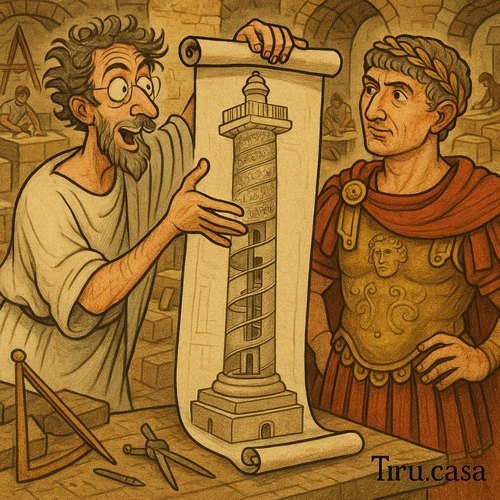

The Mastermind Architect

By 106 CE, Dacia was in the bag – so what next? Emperor Trajan wanted a stunning monument right in Rome. The job went to Apollodorus of Damascus, a brilliant (and slightly quirky) architect and engineer. He had worked for Trajan before on cities and bridges. Apollodorus took a long scroll of paper (or maybe parchment!) and rolled out the grand plan: a towering column wrapped in a figurative narrative frieze – a bit like no one had ever seen before.

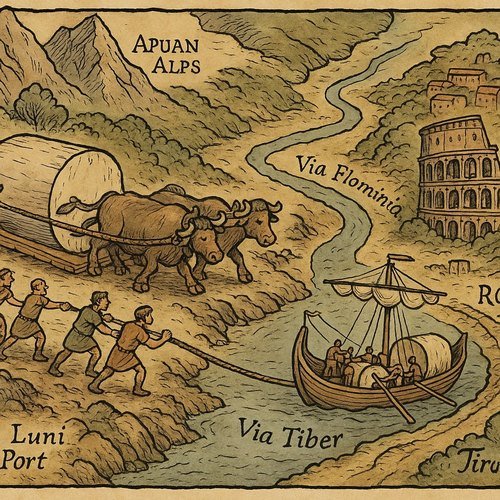

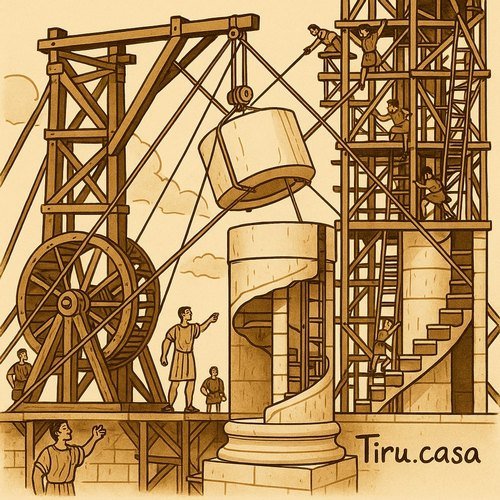

Construction Olympics

Building the Column was epic. The marble came from the Apuan Alps (near Carrara) – the same famous quarries that gave us statues of David millennia later. Huge drum-shaped blocks (some weighing up to 40 tons!) were hauled 200 miles by land and sea to Rome. According to the Museo Galileo, assembling it involved:

- Quarrying and Transport: Cut the marble, put it on ox-carts or sleds through roads down to Luni port, then by boat up the Ligurian and Tyrrhenian seas and finally up the Tiber to Rome.

- Carving: On-site or in workshops, craftsmen carved each marble slab with its slice of the story – scenes of ships, soldiers, battles, even medical corps in action.

- Raising: Erecting the column was a feat of engineering. Stories say they built cranes, wooden towers, and treadmills (think huge hamster wheels pushed by workers) to lift and rotate the drum blocks.

Even modern engineers are amazed. The Museo Galileo notes this was “a work of unprecedented complexity”. In other words: even today, experts say, “HOW?”

The Statue on Top

When inaugurated in 113 CE, Trajan’s Column was topped by a 4.5-meter-high bronze statue of Trajan himself (in armor, saluting). So it crowned the story-telling coil. (Later on, around the 1500s, this was swapped for a statue of St. Peter by Pope Sixtus V.)

Chapter 6: The Frieze – Spiral Stories in Stone

A Stone Comic Strip

Imagine grabbing a pencil and paper, drawing a long story as a comic book, then wrapping that paper into a spiral around a giant pillar. That’s essentially what the Column’s artists did! The carved ribbon is about 200 meters long (that’s the length of two football fields) with over 150 separate scenes. If you unwrapped it, it would stretch from one side of the Forum of Trajan to the other. And it moves upward in twelve loops from bottom to top – a real-life cartoon!

On this stone roll, you see nearly 2500 tiny figures: soldiers, horses, ships, Dacian warriors with wolf-hats, and Trajan himself (he appears many times, always calm and commanding). According to the Victoria & Albert Museum, it’s “a spiraling narrative” showing Romans and Dacians march, build, fight, sail, sneak, negotiate, plead, and perish in 155 scenes. (Yep, they used the word sneak – there’s a scene where Trajan inspects secret tunnels!)

Key Scenes to Spot

- River Crossing: Look near the base for bustling ships and pontoons crossing the Danube, plus Romans building roads on cliffs.

- Camp Life: Soldiers setting up tents and making helmets – one panel even shows a Roman field hospital (called capsarii) caring for wounded. This is a unique glimpse at ancient medicine in action.

- Battle Aftermath: One panel (scene 22 on the relief) shows Roman cavalry burning a village and deporting scared Dacian women and children (a sobering reminder of war’s cruelty). Another shows Dacian ambassadors kowtowing to Trajan.

- Trajan’s Triumph: Several scenes likely reference Trajan’s triumphal return to Rome. At the very top, he and his army have “won”, shown by statues of Victory holding wreaths, and the inscription beneath (the famous “SPQR…” on the base) drips with modesty about their giant achievement.

Chapter 7: Messages, Myths, and Modern Meanings

Imperial Message and Rumors

The official message of Trajan’s Column is clear: “Trajan was a victorious, pious and powerful emperor; Rome was supreme.” It emphasizes order and engineering (roads, forts, bridges) as much as battles. The Latin inscription on the base (still visible today) doesn’t say “Trajan destroyed Dacia.” Instead it humbly (almost anticlimactically) claims the column was made “to show how high a mountain and place had been built by such great works”. In other words, “Look how awesome our construction skills are!” Trajan even became the first Emperor to put his tomb in a column, mixing victory cult with ancestor worship.

Folklore vs. Fact: Over the centuries, people have spun stories about Trajan’s Column, some fanciful and some nationalistic. For example:

- Some legends (mostly in Romania) fancifully connect the column to hidden treasures or ghosts of Dacian ancestors. In reality, archaeology and history show no secret tunnel or curse – just a sturdy stone column!

- Others joked that because Trajan was so beloved, his spirit still gazes down from the top (though actually the column’s statue is now St. Peter, and Trajan’s ashes are indeed at the base, as Roman historians Eutropius and Cassius Dio recorded).

- The idea that Trajan’s Column might one day crumble and topple is pure rumor; the monument has survived nearly 2000 years with surprisingly little change (Roman builders left the joints un-mortared, yet it still stands strong against earthquakes). Modern experts marvel at how precisely the blocks were cut that no mortar was needed.

A Symbol for Romania?

What does this ancient Roman column have to do with Romanian identity? A lot, actually. When Romania was forming as a nation in the 19th–20th centuries, scholars and politicians looked back at the Dacians and Trajan as distant ancestors. The V&A notes the column is “a culturally significant monument for Romanian history and identity”. For Romanians, Trajan’s conquest meant their region was forever linked to Rome. The spiral carvings on the column are “the first ever pictorial record of the inhabitants of [modern] Romania” – a visual echo that Romanians are descendants of those ancient Dacians and Romans mixing together.

Today, Trajan and Dacian symbols show up on Romanian stamps, currency, and even sports logos. There’s a plaster copy of the column in London’s V&A Museum (cast in 1864) which was set up partly thanks to Romanian interest. Romania’s National History Museum often hosts exhibitions on the Dacians and Trajan. In a way, Trajan’s Column has come full circle: an original Roman propaganda column is now a proud piece of shared heritage.

Throughout all this, Trajan’s Column still stands in Rome, just as it did in 113 CE — a 39-meter-high spiral of stone storytelling. It has survived lightning, looters, and even earthquakes. Today, it remains a timeless reminder that history can be carved in stone — enduring, detailed, and ready to be read by any curious eye.

Citations:

- Microsoft Word - Master's Thesis Final.docx

- Trajan’s Column: 1900 years • V&A Blog

- Trajan's Amazing Column | National Geographic

- Trajan's Column

- Cassius Dio — Epitome of Book 68

- Trajan's Column: An Unyielding Pillar of Imperial Strength

- Dacians and Sarmatians: Reliefs on Trajan's Trophy at Adamclisi

- Trajan’s Column

- Trajan Column

- Hadrian's Rome: Hadrian's Rome: 3 Death, divinity and the emperor | OpenLearn - Open University

- Trajan's Column - Legio X Fretensis

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0