21 May 1821: The Betrayal of Tudor Vladimirescu at Golești – Truth, Myths, and the Fight for the Soul of Wallachia

On May 21, 1821, the bold Wallachian leader Tudor Vladimirescu was arrested at Golești and handed over to Alexandru Ipsilanti — a moment of betrayal wrapped in myths, politics, and broken alliances. This vivid, all-ages project blends historical truth, lesser-known facts, and rich illustrated storytelling to uncover what really happened that day, how it shaped future Romanian identity, and how his image was later twisted by communist propaganda. A powerful journey through time — vibrant, revealing, and deeply human.

Pandur Pandemonium: Tudor Vladimirescu’s 1821 Revolution

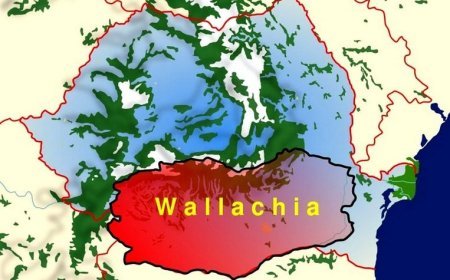

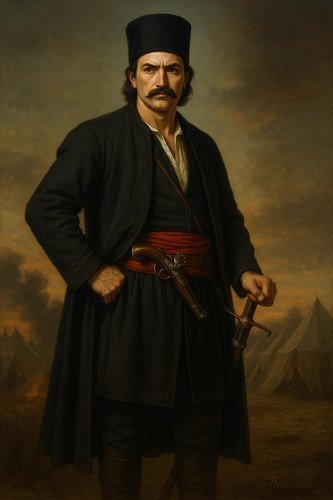

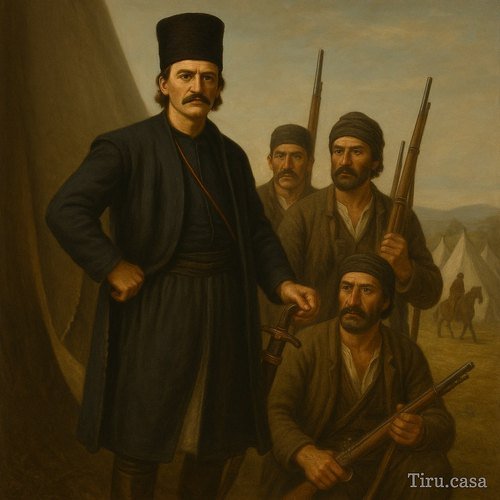

Wallachia in 1821 was a cauldron of tension. Two centuries of Phanariote rule – Greek princes appointed by the Ottoman Porte – had left the Principalities overtaxed and frustrated. Peasants and even conservative boyars had grown tired of fat-titled Greeks treating Wallachia “as an actual tenancy,” reaping heavy taxes in short stints. In this climate, a folk hero emerged: Tudor Vladimirescu, born c.1780 in Oltenia. A former soldier (he served in the Russian-Turkish War of 1806–12), Vladimirescu was charismatic and savvy. By 1819 he was quietly in contact with the Greek revolutionary society, the Filiki Eteria, which promised a common cause against Ottoman oppression. He built a force of Oltenian pandurs (irregular militia) and envisioned sweeping reforms: “the homeland is called the people,” he famously proclaimed, stressing freedom and rights for the poor.

1. Background: Phanariotes, Pandurs and the Age of Revolutions

For a century, Wallachia’s Greek rulers kept most real power in Phanar networks. Ottoman governors (Phanariotes) taxed the land heavily, fled quickly and left “excessive fiscal policies” in their wake. Pandemic outbreaks and banditry sometimes flared under weak rule, so local leaders like Tudor used peasant martial traditions (the pandurs were originally elite foot-soldiers) to maintain order. By 1820–21, similar nationalist stirrings in nearby Greece spread: Ypsilantis’ Eteria had begun an insurrection in Moldavia (spring 1821). In this World of Revolutions, even Wallachian boyars and priests were whispering of an end to Phanariote privilege. Vladimirescu’s move was partly anti-Phanariote (backed by conservative boyars), but it quickly took on broader themes of Romanian independence and social justice. (Importantly, Tudor’s revolt was not aimed first at Istanbul – it began as a protest against corrupt rule, not outright secession.)

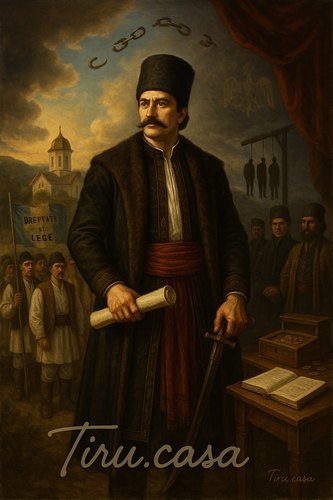

2. Tudor Vladimirescu: Soldier, Peasant-Leader, Prince?

Tudor’s life before 1821 was a study in determination. As a young man he served in the Russian army during the last Russo-Turkish War, absorbing Enlightenment ideas and seeing the Greeks’ desires for nationhood. After the war, he returned home to Oltenia and quietly gathered a loyal band of pandurs: tough, rifle-armed troops used to frontier life. Wealthy boyars noted his charisma and cunning negotiation skills. He even learned Greek to deal with Phanariote clerks, but reportedly needed a translator at meetings with learned officials (the Archpriest Ilarios of Argeș often spoke for him). Though unpretentious in origin, Tudor was ambitious: on capturing Bucharest, he started wearing the princely kalpak (fur hat) and demanded to be called “Domn” (Prince), an early hint that he saw himself as more than just a rebel.

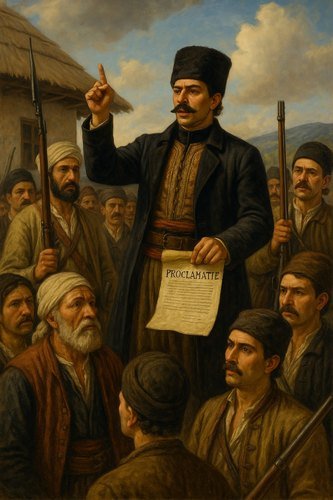

“[…] Tudor Vladimirescu se adresează pandurilor și țărănimii cu o proclamație revoluționară, promițând că va împărți ‘averile cele rău agonisite ale tiranilor boieri’ și va pune capăt abuzurilor, aducând slobozenie și ușurare sarcinilor.”

Like a folk tale hero, he spoke plainly. His Padeș Proclamation (23 Jan 1821) invoked the right of all “mílitated people” to resist oppression and promised “spring” would follow the “winter” of peasant misery. He directly addressed the villagers, calling on “our poor downtrodden people” to rise against their “tyrant boyars,” while promising his own pandurs (the elites of his army) that their privileges would be restored. (In other words, Vladimirescu courted the panduri as brothers while rallying the serfs to a share-the-wealth plea.) He also aimed big: he demanded end to bribery in office appointments, heavy tax cuts, and even formation of a native Wallachian army – reforms well ahead of their time. By January 1821 he had set the stage for revolt, blending Enlightenment words (“il diritto a resistere oppressione”) with fiery populism.

3. The Uprising Begins: Summer 1821

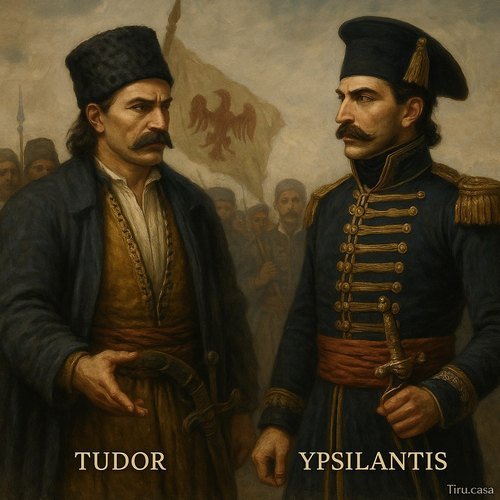

In February–March 1821 Tudor’s largely peasant army marched on Bucharest (then the capital). Unlike a cartoon gladiator, he did not try to slaughter opponents indiscriminately. Instead, he took power by negotiation: the Phanariote Prince Callimachi fled and Vlad’s pandurs occupied the city on 21 March. Here he issued another decree espousing peace with the Sultan – he never declared outright war on the Ottomans. Meanwhile his Greek partner Aleksandros Ypsilantis (prince of Moldavia and head of Filiki Eteria) also arrived in Wallachia with a small “Sacred Band,” hoping to unite Orthodox peoples. Initially they struck a deal: Vlad would control Oltenia and southern Muntenia, Ypsilantis would oversee Moldavia and northern Muntenia.

However, the alliance was uneasy. Ypsilantis’s Eterists wanted the whole country for the Greek rebellion, and harshly treated both Muslim and Romanian clergy when they suspected disloyalty. Tory defector Tudor refused to condone terror: he clashed with the Greek discipline, even hanging some of his own men who looted or threatened civilians. Meanwhile, international politics shifted: the Russians did not join the Greek cause as planned (Tsar Alexander had recently become suspicious of Ypsilantis), and a large Ottoman army massed nearby to put down any insurrection. Feeling betrayed by the stalled foreign aid, Tudor quietly abandoned the joint plan. He still allowed Ypsilantis’s men to hold Bucharest, but declared his own neutrality in the face of the advancing Turks. In effect, he broke with his Greek allies and tried to bargain for Wallachia’s future on his own terms.

4. “Spring of Betrayal”: The Arrest on May 21, 1821

This is where the Pandora’s box truly blew. Tensions boiled over during a meeting on May 20: Vlad insisted on keeping control of Oltenia without Greek interference, Ypsilantis insisted on following his original joint command. Into the night of May 20–21, Tudor’s camp lay just outside Golești (in Argeș County). On dawn of May 21, in a sudden move arguably as swift and surprising as a cartoon ambush, Ypsilantis’s officers (possibly influenced by the Eterist leaders or even Ottoman informants) arrested Tudor in his gazebo. He was handcuffed and secretly flown by boat to Târgoviște.

“1821 – Tudor Vladimirescu, conducătorul Revoluției de la 1821, a fost arestat în tabăra de la Golești și predat lui Alexandru Ipsilanti.”

The Greek revolutionary leader turned Vladimirescu over to his own troops for a swift trial. He was accused of treason – specifically, collaborating with the Ottomans (though that charge remains historically dubious). Over the night of May 27–28, Tudor was tortured and killed by Ypsilanti’s men in Târgoviște. His mutilated body was thrown into a cesspit – an ignoble end for a man many peasants considered their liberator.

This betrayal was chilling. Even an Ottoman official’s dispatch records his capture flatly as “stopping the monastery where Ypsilantis sought refuge, and to arrest ‘Todori (Tudor) and other runaway bandits’”. The language makes it clear how the Porte’s officers viewed him – as mere brigand and traitor. In the very stamp of black humor befitting this chapter, note that the date 21 May has odd echoes in history: in Ancient Rome it was also the Agonalia festival for the god Vediovis – perhaps an omen for gods listening. (In modern times May 21 is ironically World Day for Cultural Diversity and International Tea Day – a reminder that global calendars can play jokes on history.)

5. Immediate Aftermath and Ottoman Reaction

With Tudor dead, the revolt fell apart. The Ottomans occupied Bucharest unopposed, crushing the remaining pandurs. Curiously, they liked one outcome: the Phanariote experiment was over. By early 1822, the Porte installed loyal Wallachian boyars as Princes – Grigore IV Ghica in Wallachia and Ioan Sturdza in Moldavia – ending Greek dynasties in the Principalities. Thus ironically, Vladimirescu’s uprising (though defeated) achieved its goal of anti-Phanariote reform. Russia later made its own gains in 1828–29, leading to a semi-constitutional regime (Regulamentul Organic) in both Principalities. But for a few years, Wallachia remained under heavy Ottoman (then Russian) occupation, and the old social order mostly rebounded.

6. Tudor’s Real Ideals vs. Later Doctrines

Underneath all the politics, what did Vlad truly want? Historical records suggest he was not a socialist by any means. He was a shrewd survivor: he saved money while serving a boyar, opened accounts, and gave gifts to influential patrons. He demanded privilege for his own Pandur corps, and in practice negotiated (even with the enemy) to protect Wallachian interests. His proclamations framed the “people” as supreme, yet he never advocated communal land – rather, modest tax relief and removal of corrupt elites. In short, his real ideals combined rural nationalism and meritocratic reform (merit-based offices, less extortion), not the class struggle of later communism.

A recent historian, Tudor Dinu, puts it bluntly: Vladimirescu “was quite different from the one we know from old history books”. Communist-era textbooks loved to call him “hero of the poor against the rich”. But Dinu notes that Vlad actually accumulated wealth as an estate manager and was capable of generosity toward some boyars; he was no grim ascetic peasant-fighter. He claimed to fight “for the rights and freedoms the people deserved”, and indeed did aim to relieve peasant burdens – but he also liked order and even carried out military discipline by hanging looters in his own ranks.

In other words, do not confuse Tudor’s plan for a proto-nationalist reform with later Marxist ideology. He was orthodox (both in faith and in allying with Russia), he wore a prince’s hat, and wanted legal equality, not class war. After his death, this complexity was swept away by simplistic myths.

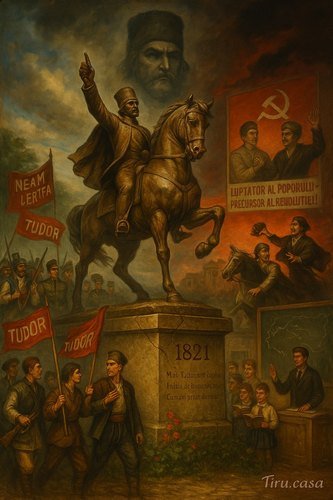

7. Legacy and Myth-Making (1821–1945)

In the 19th century, Romanian patriots like historian Nicolae Iorga framed Tudor’s revolt as the dawn of national awakening. Folk ballads and local memory cast him as a defender of “slavery of the boyars” – some villages in Oltenia still sing “Cântec Tudor” about him today (a reminder of how revolutions become legend). But it was during the 20th century that Tudor Vladimirescu’s image truly exploded in propaganda, for very different reasons:

- Fascist/Nationalist Era (1930s–’40s): Iron Guard and other far-right groups of Greater Romania looked back at 1821 as a glorious “revival of national spirit.” They gave the Pandurs cult status as anti-foreign heroes, even naming units or marches after them. At the same time, left-wing opponents (Radical Peasants’ Party, early communists) also claimed Tudor as a “man of the people,” mustering Pandur reenactors at rallies. Thus even interwar politics showed how he could be co-opted on either side.

- Communist Era (1945–1989): The new regime in Bucharest fell in love with Tudor Vladimirescu – but on their terms. Official historiography glossed over his break with Greece and with Russia. Soviet-friendly accounts lumped him and Ypsilanti together as “liberators of the Balkans” backed by St. Petersburg. In the 1950s–60s, academics even spun wild theories: one party historian claimed the 1821 revolt was secretly inspired by Russia’s Decembrist uprising, while blaming English “agents” for killing it. Ceausescu’s nationalist-communist blend kept Vlad’s heroic status alive: in 1966 he created an Order of Tudor Vladimirescu, the third-highest decoration of the People’s Republic.

One particularly famous example: the 1962 film “Tudor” (dir. Gheorghe Vitanidis) turned Vladimirescu into a cinematic martyr. In the movie he escapes dramatically from Assassination by leaping from his horse after a shot, uttering “I return like the grass of spring” in death – a peaceful, poetic end invented for the screen. (In reality his death was far more brutal.) Screenwriters even erased his quarrel with the Greeks and recast him as an early champion of nationalisation and class struggle. The film’s gloss made the heroes clearly anti-Ottoman and anti-capitalist. As national communism rose in the 1970s–’80s, Vladimirescu was touted as a “fighter of the poor” and “predecessor of socialist revolution,” regardless of what he had actually meant. Every schoolchild learned him as a peasant-general allied with Russia, which conveniently justified Romania’s Soviet alliance – a far cry from the autonomous Wallachian leader he had been.

8. Folk Memory, Festivals and Trivia

Despite the political spin, Tudor Vladimirescu remains a vivid figure in Romanian folk memory. There are doinas (folk laments) that recall his name, and even a national folklore festival in Mehedinți called “Tudor Vladimirescu – cântec, doină și baladă” held in his honor each year. Statues of him stand in towns like Târgu Jiu (often with dramatic poses worthy of superhero comics). The story of Golești has its own micro-myth: a museum notes that Vladimirescu’s camp spanned Golești plain from May 18–21, 1821, and that the little pavilion (“gazebo”) where he rested was later dismantled and carried off to Târgoviște as part of the betrayal. (Imagine a cartoon where the hero’s camping tent is literally whisked away in the night!)

9. The Date May 21 in Context

The day of Tudor’s arrest, 21 May, has little obvious symbolism in itself – except what history attaches to it. We’ve mentioned the pagan Roman festival Agonalia to Vediovis on that date. Two centuries later, 21 May also marks modern celebrations: UNESCO’s World Day for Cultural Diversity and International Tea Day (which might have left Tudor smiling if he had known). Even Shakespeare noted, “so all a time the sun” on May 21 would rise – though that line can’t be strictly Latin-quoted, Tudor surely would have loved the concept of carpe diem.

In Romania today, 21 May is often remembered via calendars or kids’ history quizzes as “the day Vladimirescu was arrested,” treating it like a national remembrance day. Among historians, it’s also an open question: what if Ipsilanti had trusted Tudor a little longer, or if the Russians had intervened? Those “what-ifs” add mystery: “Et tu, Ipsilanti?” one might lament, borrowing Caesar’s own question in Latin. In the end, May 21rd remains a pivot – a day when one man’s spring of hope abruptly turned into an autumn of betrayal.

10. Legacy: Identity and Politics

The 1821 uprising, though crushed, laid cornerstones for Romanian identity. First, it ended Phanariote rule and affirmed the idea that Wallachians should be led by their own – setting precedent for later 1848 and independence struggles. Second, Tudor’s emphasis on the people (“poporul”) and fair governance fed the nationalist narrative that România era destinată să fie liberă (“Romania was destined to be free”). Leaders from 1848 revolutionaries through 1918 Great Union politicians claimed his legacy: Bălcescu called him a “peasant rebellion,” Iorga a “national revolt.”

Yet 1821 also left an ambivalent imprint: it showed how easily the national cause could fracture. The Tudor–Ipsilanti split became a cautionary tale about foreign alliances. In communist times, lessons were rewritten: Tudor became a great socialist innovator of native democracy, glossing over how much he was not truly allied with Russia, as the Russians refused to fully support him and did not want to fight the Turks. Post-1989, some Romanian nationalists tried to reclaim him again, this time as a hero of “our own Church and land,” downplaying his momentary Greek partnership. Each era casts Tudor in its own mirror – he is perpetually both a hero and a footnote, depending on who’s telling the story.

11. Latin Quotes and Sayings

Tudor Vladimirescu’s story is rich with the kind of tragic-clash drama that makes classical parallels tempting. A Roman might have said “Salus populi suprema lex” – “The welfare of the people is the highest law” (Cicero) – a sentiment Tudor seemed to believe in, as he repeatedly invoked the people’s need. After his betrayal, one might mutter “Dum spiro, spero” – “While I breathe, I hope,” reflecting how Tudor clung to hope of Russian support until his last breath. When the Eterist stabbed him in the back, the viewer could not help but think of Caesar’s “Et tu, Brute?” – even if said to Ypsilanti instead of Brutus. And from the noble quiet of being a martyr, we might whisper “Sic transit gloria mundi” – “Thus passes the glory of the world,” as the glory of Vladimirescu’s uprising passed in a single dark night. These Latin echoes remind us that history’s greatest stories often sound like ancient tragedy, even when they happen in our own backyard.

12. Questions for Further Thought

- What if Vladimirescu had allied with the Ottomans instead of the Greeks? He was accused of that, but would Ottoman support have saved him or only made him a tool of Istanbul?

- Was Tudor a true nationalist or a pragmatic local leader? Did he dream of an independent Romania, or did he simply want better rule for Wallachia under the Sultan?

- Why do regimes co-opt heroes like Vlad? Consider how Tudor’s image changed from 1821 to 1989. Do we tell history or history tells us?

- Could Vladimirescu’s reforms have succeeded if he had not been arrested? Imagine Oltenia quietly reorganized under him – how might that have changed later revolutions?

- Are Roman attitudes revealed in folklore? The ancient Romans worshipped Vediovis on May 21 – maybe Tudor’s fate shows that sometimes odd traditions die hard.

These questions invite reflection on how events echo across time. Tudor Vladimirescu’s arrest on 21 May 1821 remains a pivotal “what happened next?” in Romanian history – a dramatic turning point mixing heroism, betrayal, and propaganda. By examining contemporary accounts and later myths, we piece together not just the factual story, but the living memory of a revolt that helped shape Romania’s soul.

Citations:

- Wallachian uprising of 1821 - Wikipedia

- Tudor Vladimirescu - Wikipedia

- CEEOL - Article Detail

- Radio România Internațional - The History Show

- AGERPRES – Revoluția de la 1821: Proclamația de la Padeș

- Historia – Arestarea lui Tudor Vladimirescu

- Brill – "Those Infidel Greeks" (2 vols.)

- Roman festivals - Wikipedia

- Virtual Travel Guide – Curtea Goleștilor, Argeș

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0