The Fiery Saga of Voivode Ioan II (John II) the Brave – The Last Cry of Free Moldova against the Crescent

An epic and tragic tale of Voivode Ioan II (John II) the Brave, the ruler who, in just two years of reign (1572–1574), rose against the Ottoman Empire and defied the old boyar order through brutal reforms and an army of fire. From Iași to the blood-soaked fields of Cahul, this historical chronicle reconstructs the last cry of a free Moldova, caught between the cannons of war and betrayal from within. A battle engulfed in fire, blood, and impossible choices, in which a controversial voivode — as feared as he was admired — gambled his fate and left behind a legend torn between truth, myth, and memory. An unvarnished, authentic portrait of a leader who dared to say “no” to the greatest empires of his time — and paid the ultimate price.

Voivode Ioan II (John II) the Brave – The Iron Raised from Betrayed Soil

The true story of a reign torn between courage, betrayal, and death

Ioan II Vodă the Brave (1521–1574), also known as Ioan the Armenian, remains one of the most controversial and remarkable medieval rulers of Moldova. Reigning only from 1572 to 1574, he sought to consolidate Moldova’s throne through drastic reforms and military strengthening, while the boyars accused him of cruelty. During his short reign, he moved the capital to Iași, introduced copper coinage (to stabilize the economy), and assembled an impressive artillery — over 110 cannons.

Despite the victories at Jiliște (1574) and Tighina, the betrayal of Hatman Ieremia Golia changed the fate of Moldova. In June 1574, at the battle of Iezerul Cahul (near Roșcani), the Moldavian army — outnumbered and caught in a torrential rain that soaked their gunpowder — retreated near the village of Roșcani. Ioan Vodă surrendered to spare his troops, but the Turks killed him in a gruesome manner: he was beheaded, and his body was torn apart by camels. Parts of his remains were taken by the enemy as talismans.

This historical event, remembered in contemporary chronicles and in medieval works from Poland, Germany, and Italy, completes the complex image of a remorseless voivode, judged both as a visionary military hero and as a brutal tyrant. In this narrative project, we will explore step by step the historical path of Ioan Vodă — from the European context of the 16th century, to the battles along the Danube and their long-term consequences, seen through the eyes of contemporaries and modern historians. We will not shy away from highlighting the myths and propaganda — whether nationalist, communist, or religious — that have shaped his image over time. Because the truth, no matter how harsh, deserves to be told even to the young: a medieval ruler is not merely a prince or a hero, but above all a man, with actions, weaknesses, and real consequences for history.

🎬 The Spark of a Destiny: The Historical Significance of Ioan Vodă the Brave

Ioan Vodă did not appear on the stage of history as a fairytale hero, but as a bold adventurer in a Europe shaken by great powers and religious conflicts. In the spring of 1572, he was chosen by the Moldavian boyars (with the blessing of the Ottoman sultan) as voivode of Moldova, at a time when the Ottoman Empire, the Kingdom of Poland, the Tsardom of Russia, and the Kingdom of Hungary were all vying for supremacy in the East. The replacement of Bogdan Lăpușneanu and the enthronement of Ioan were driven both by internal divisions — the boyars resented central authority, and some sought support in Poland — and by international context, such as Polish fears that Bogdan leaned too heavily toward Ottoman influence.

In this unsettling atmosphere, the life of Ioan Vodă becomes a lesson in how fragile the balance of power can be — between ruler and boyars, and among neighboring states. He himself was an exotic figure: the illegitimate head of a ruling line (son of Ștefăniță Vodă, the illegitimate son of Stephen the Great) and of partial Armenian descent. Raised in exile — wandering through Poland, Crimea, the Ottoman Empire, and even the Holy Roman Empire — Ioan Vodă even changed his religion depending on circumstance. He brought to Moldova the vision of a strong and centralized government, in stark contrast to the fragile relationship between the feudal boyars and the princely throne.

This context is illustrated by the chroniclers of the time: for instance, Azarie notes that the boyars welcomed him with joy when he arrived in Moldova in February 1572. But as his reign progressed, Ioan pursued a policy of strengthening princely authority — confiscating the wealth of overly “greedy” boyars and crushing any rebellion (and the boyars called him “the Terrible” because of his cruelty). This extreme harshness, however, translated in that era into hope for peasants and poor clergy: though merciless with the boyars, Ioan Vodă redistributed land and aid to common people, trying to build a more unified country around the voivode — a project which, as historian B.P. Hasdeu noted, resembled the later reforms of Cuza.

In conclusion, why does Ioan Vodă’s struggle still matter today? Because in the small Romanian principalities caught between great empires, he stands as the image of a ruler fighting to preserve his independence. His story — from his early foreign battles in childhood to his final breath on the battlefield — reflects the political and social movements of an entire era. Like in a legend, Ioan departs from Adrianople at the call of the boyars (February 1572), only to end up in the graveyard of the fields near Cahul — far from the warmth of Constantinople. This oscillation between the dream of absolute power and a tragic end reminds us that history is not just a sequence of objective dates, but a series of human experiences, full of emotion and consequence — like any other meaningful story about courage, betrayal, and destiny.

🏛️ Times of Iron and Gunpowder: The Historical Context of Voivode Ioan the Brave

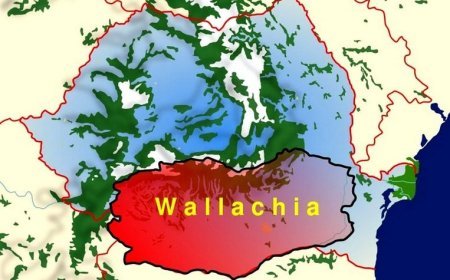

In the Europe of 1572, chroniclers spoke of political fires blazing across the continent: the Kingdom of Spain was reaching the height of its global dominance, the Kingdom of France was trembling in a religious war between Catholics and Huguenots, and over Moldova reigned Selim II, a drunken sultan on the decaying throne of the Ottoman Empire. Wallachia and Moldova had long been under Ottoman authority, paying tribute to the Porte, yet populated by Orthodox peoples who still dreamed of defending Christianity. In such times, the power of a small ruler could matter more than one might think: Ioan Vodă’s success depended both on the internal elite and on diplomacy with neighboring states.

Domestically, Moldavian boyars dominated politics through networks of serfs and vast estates, often ready to spit on any principle of centralization. When weak rulers took the throne, the boyars felt free to exploit: indebting the population, enriching themselves, and casting their gaze toward support from Poland or the Habsburg Empire. After the long reign of Stephen the Great, Moldova suffered a string of weak voivodes (such as Bogdan the Lame, Ștefăniță, or Petru Rareș) and embarrassing episodes of submission under Ottoman suzerainty. These periods of instability left deep wounds in society: poverty and fear among peasants, and growing discontent within the Church and segments of the nobility. As an illegitimate prince and adventurer, Ioan Vodă understood he could never earn the loyalty of the boyars—only their respect through military force.

Externally, Moldavia was a fragile flank caught between clashing empires: to the northwest, the Kingdom of Poland hunted for regional supremacy; to the northeast, Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia dreamed of access to the Black Sea; and to the south and east, the Ottoman Empire demanded submission and loomed constantly with the threat of force—ready to swallow the entire Romanian territory.

In 1572, Ioan Vodă officially secured the Sultan’s support—receiving the title of Voivode of Moldavia in the palaces of Adrianople on February 15—but in return, he pledged tribute and strategic loyalty. Was this a religious or cultural revolt? Not quite. Ioan was pragmatic: he changed his religion based on circumstance, converting to Orthodoxy only shortly before claiming the throne—an essential requirement to rule Moldavia.

Politically, he maneuvered deftly among his neighbors: he hoped for Polish backing (having already attempted to claim the throne after Lăpușneanu’s reign), maintained ties with the Tatars of the Khanate of Kazan, had noble connections with German circles, and kept a formal friendship with the Ottomans.

Yet his true ambition was independence: he refused to pay Ottoman tribute and encouraged open confrontation—a decision that would lead directly to the war of 1574.

Thus, the deeper context of Ioan Vodă’s reign includes the late Renaissance era—a time when rulers of the Romanian principalities were learning that they could no longer govern solely with the sword and the advice of boyars, but had to embrace cannons and professional soldiers. (In fact, Ioan would go on to strengthen his army in ways unmatched by any medieval Romanian ruler before him.)

At the same time, Moldavia was torn by internal strife between the “head of the country”—the boyar elite—and the newly installed prince. In modern terms, one could say that Ioan Vodă enacted an authoritarian reform: he challenged the privileges of the nobility, built a professional military, and administered the state directly, spending significant sums on artillery and personally overseeing the princely chancery.

The result was a powerful ruler, feared by the old boyar class but admired by many of the poor and by his soldiers. And when the boyar conspiracies left him isolated and under-resourced, the great Ottoman enemy gave him the chance to prove what he could do when truly threatened—what follows is nothing short of a historical whirlwind.

⚔️ Between Battlefields and Betrayals: The Reign and Wars of Ioan Vodă

The story unfolds in two major acts. The first act (1572–1573) is that of internal consolidation: Ioan reorganized the army, raised taxes but favored peasants and clerics (taking from some, giving to others), moved the capital to Iași – perhaps because he felt that Suceava, though steeped in glory, lay too close to old ruins and too far from the path of trade and renewal; perhaps because Iași, more sheltered and more strategic, could become not only a shield but also a symbol of a new Moldova. He minted a new copper currency – not for show, but for balance, to stabilize an economy torn apart by tributes, boyar theft, and fiscal chaos; he wanted a simple coin, yet one with weight – a root cast in fire, a beginning of autonomy, a step toward economic sovereignty in a country drained by foreign-imposed obligations. Contemporary documents called him “the Terrible” precisely because he did not hesitate to punish the corrupt boyar class in every way: a bishop was burned at the stake for defiling the priestly robe, and the boldest among the nobility were buried alive or broken on the wheel.

Still, Ioan Vodă did not rule from an ivory tower. Many distrustful boyars were plotting to remove him and install Petru Șchiopul (the brother of Alexandru Mircea of Wallachia) on the throne. In the spring of 1574, this conspiracy turned into a full invasion: from the southwest, Alexandru Mircea of Wallachia and his brother Petru, backed by the Ottomans, crossed the Danube and entered Moldavia to overthrow Ioan. Ioan Vodă struck back, allying with the Cossacks of Zaporizhzhia and marching into open battle in a series of rapid confrontations. Thus, in April 1574, the Moldavians caught and crushed Alexandru Mircea at Jiliște (in the area of Râmnicu Sărat). Following this victory, Ioan turned his army against the other two conspirators. In a sharp and theatrical exchange—worthy of today’s historical dramas—the Moldavian ruler declared: “I’ll deal as I must with the prince of Wallachia, and shake the rest of you like hot coals!” Ioan then installed Vintilă, a loyal boyar, in Târgoviște, and marched toward Brăila, where Petru Șchiopul had taken refuge. A battle was fought at Brăila, where Ioan Vodă once again emerged victorious—settling accounts with Petru for good—before heading with the Cossacks to reinforce the front on the Dniester.

The Foundation of Heavy Firepower: During this period, Ioan Vodă proved just how visionary (and powerful) he was in military matters. He studied the methods of war used by the Turks, Tatars, and even the Germans and Poles, realizing that the future of the battlefield lay in modern artillery—cannons. Thus, he assembled in Moldova hundreds of lightweight, maneuverable cannons, designed for agility — a kind of 16th-century blitzkrieg, waged with the precision of David’s sling.

In a Europe where even the greatest kingdoms boasted no more than 30–40 cannons, Ioan Vodă gathered over 110 — most of them forged in Moldova, based on blueprints he personally selected. This firepower would have stirred envy even among the proud soldiers of Stephen the Great. He brought in master gunsmiths, ordered the local production of gunpowder and cannonballs, and prepared for the great war to come.

The Battle of Lake Cahul (June 10–14, 1574): The second major phase came in the summer of 1574, when Sultan Selim sent a large Ottoman-Tatar army toward Moldova, like a storm of bullets, to crush the rebels. Ioan Vodă, proud of his artillery and confident in the courage of the Moldavians and his Cossacks (who always brought the Tatars to their knees from afar with firearms), went out directly to the battlefield near the lake at Cahul. Initially, the battle seemed to turn in Moldova’s favor: the Moldavian cannons shattered the Ottoman cavalry, and the Moldavian infantry and the Cossacks decimated many Turkish formations. But with the odds turning, even after a heroic counteroffensive in which they captured and destroyed around 60 Ottoman cannons, a heavy summer rain soaked the gunpowder and rendered the artillery useless: Ioan’s cannons could no longer fire. At the same time, the Moldavian cavalry, led by Ieremia Golia (Ioan Vodă’s hatman), committed the most shameful betrayal: at the beginning of the battle, Golia and his men turned their weapons and joined the Turks, leaving the prince without his most experienced fighting corps. In just a few hours, the balance of forces became overwhelmingly unfavorable – about 1 to 3 against the Moldavians.

The decisive moment occurred on June 10, when the treacherous Moldavian cavalry fled toward the Turkish army, while the Romanian cannons were still wreaking havoc among the enemies. Only then did Ioan Vodă, seeing the sky darken and the Ottoman forces charging fiercely, order a retreat to the fortified camp near the village of Roșcani. On June 14, 1574, after four days of fierce fighting, defending the position under relentless gunfire, the voivode was forced to surrender, requesting in return the lives of his soldiers. But the Turks did not keep their word: they killed him with unimaginable cruelty. According to Polish eyewitnesses (Bartholomew Paprocki and Leonhard Gorcki), a macabre torture followed: his body was torn apart, tied to the tails of camels, and the Ottomans collected the pieces like talismans of bravery. Thus ended, in dreadful agony, the life of Ioan Vodă the Brave, voivode and warrior, on the battlefield of Roșcani.

📉 What Followed on the Battlefield and Through the Ages: Immediate Consequences and Lasting Legacy

The death of Ioan Vodă had an immediate and devastating effect: it marked the end of medieval Moldova’s military glory. The Moldavian army, demoralized and plundered by bandits, was decimated; the entire Principality was left at the mercy of the Turks and the traitorous boyars, who reclaimed their lost privileges. His very own son, Petru (known as Ștefan the Deaf), would be installed as ruler in Bucharest in 1591 – proof that the blood of Ștefan cel Mare still produced voievods, though Moldova would never again have a leader as strong.

Shortly thereafter, within just a few years, the sultan installed in Moldova a succession of "tolerated" rulers – many of them of Tatar or Ottoman origin – who paid tribute and accepted full submission. The country transformed from a bastion of resistance into a customs territory, losing more and more of its autonomy. In a grotesque twist, even the traitorous boyars – such as Marcu Golia, cousin of Ieremia – were rewarded with official titles and estates, and Ioan Vodă's wealth was divided among the new officials with feudal-agricultural functions.

In the long run, however, the military and administrative vision of Ioan Vodă remained in memory as a beacon of hope. His reforms, however harsh they may have seemed, outlined an alternative path for the Romanian principalities: the model of a state firmly ruled by a voievod and supported by a centralized army – an idea that would later take shape under Mihai Viteazul. After Ioan’s fall, Moldova went through decades of instability, poverty, and excessive taxation (the obsession with tribute becoming the norm), until, at the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the Phanariot era, legendary figures of brave rulers reappeared, such as Mihai Vodă or Constantin Brâncoveanu. Quite ironically, the ‘invention’ of the mucarer – a fiscal agent who collected taxes through coercion, introduced as a solution to the lack of a local bureaucratic corps – was also brought into Moldova after Ioan’s reign, and was, strangely enough, viewed as an indirect legacy of his idea of a vigilant and well-organized state.

Beyond what happened immediately, Ioan’s death on the battlefield remains a symbol: the bloodstained seal of a defeated Christendom. In 1591, when Constantinople set the path for Ștefan Surdul (the son of Ioan) to become voievod of Wallachia, foreign ambassadors were still recalling the macabre episode: “Voievod Ioan Vodă was torn into four and hung from four camels” – a sort of mythical warning for any future ruler, steeped in the cruelty embraced by Ottoman tradition. And nothing speaks more painfully than the fate of a voievod cast to the margins of history – still bound to the world of Romanity by a trace of Basarabian blood, yet fallen into legend at the end of the road.

🔍 Ioan Vodă in the Mirror: Perspectives and Diverse Interpretations

The image of Ioan Vodă cel Viteaz is like a kaleidoscopic prism. For his Christian contemporaries, he remained a bitter blend of “the Terrible” (for the boyars and high clergy – the ruthless executioner of the nobility) and “Ioan Vodă the Armenian” (a reference to his maternal origin). And over the centuries, interpretations have indulged in nuance. Some historians see him as a misunderstood hero, others as a visionary tyrant, and still others as a man thrust onto the throne by the usual luck of adventurers throughout history. As the newspaper Adevărul writes, “some consider him a military genius, others – a hero, while others see him as a cruel and monstrous individual.”

The confrontation between old and new perspectives reveals the nuances: chroniclers of the time, such as Grigore Ureche, acknowledged his bravery on the battlefield but seldom mentioned Golia’s betrayal, preferring instead to emphasize that the Moldavian troops could not have stopped the invasion anyway (thus conveying the idea that “such was fate”). In any case, Ureche and other chancery chroniclers (Costin, Miron Costin) were rather harsh in their portrayal of him, accusing him of tyranny and greed toward the punished boyars. On the opposite end, in the 19th century, nationalist romantics proclaimed him “cel Viteaz” (the Brave): Bogdan Petriceicu Hașdeu, for instance, elevated him in 1865 to the status of a social visionary (a forerunner of Cuza), while postwar communists portrayed him as a defender of the peasants against the boyars – almost an ideal precursor of “the path toward socialism.”

Of course, this entire history is not “black and white.” For example, even foreign contemporaries left mixed accounts: Bartholomeu Paprocki, a Polish monk from Kraków, praised Ioan’s bravery in battle against the Turks, but also noted that he was “infamously betrayed.” Leonhard Gorcki (a German traveler) wrote the most detailed journal about his reign, describing in the harshest terms how Ioan fought Selim on equal footing—until the hatman Ieremia gave him his word of honor and then stabbed him in the back. Thus, even Western chroniclers do not hesitate to morally assess the conduct of the characters: Golia is compared by modern historians to Judas, for “for thirty bags of gold, he sold a friend and a homeland.” Our current perception therefore remains mixed: Ioan Vodă appears now as a kind of “medieval Rambo general,” and the conclusion is that he confronted the Turks as no other Romanian prince of his time did—but paid dearly for his fiercely independent warrior spirit.

In the end, every interpretation must be taken with a grain of doubt. We can honestly acknowledge that our main source—the chroniclers of the time—were all partisans (either boyars or clerics), and that they either erased or embellished the truth in favor of their own class. Yet the brutal facts, such as the killing of boyars or the torture of prisoners—described in hallucinatory detail in Ottoman and Polish sources—cannot be denied: history was written in blood. The man Ioan Vodă remains, with both virtues and flaws: a scholar in mind, a tyrant in deed, a visionary in vision. As for us, the contemporary readers, we may ask ourselves how things might have unfolded “if Ioan had lived longer,” but we must admit that his end remains, even today, a universal warning: like others who dared without weighing the cost of defying the powerful, Ioan Vodă paid with his life for a gesture of territorial dignity, ultimately becoming a legend of the Nation.

Dacian Cradle or Pehartic Shadows?: Connections to Dacia and Modern Romania

It is tempting to see Ioan Vodă as a “heir of Dacia” or of the Romans, since he embodied the Romanian voivodal customs of his time. However, in reality, the direct connection with ancient Dacia is missing – he is a figure of the Middle Ages, more than 1500 years after the Dacian era. The idea is rather cultural: he was shaped by the legacy of Ștefan cel Mare (his great-grandfather) and, through the bearings of fate, positioned himself within the line of Moldavia’s “Basarabian forefathers,” also inscribing himself in the early movements for Romanian unity.

The true “Thracian-Dacian legacy” that we can attribute to him is rather moral: his often-shifting religious obedience (Armenian mitre, then Polish Catholicism, Lutheranism, Islam, and finally Orthodoxy) reflects the intercultural compromises of his times – a kind of foreshadowing of modernity, not a direct symbol of Dacianism.

In the modern era, national movements reinterpreted his figure as they saw fit. In the 19th century, Moldavian liberals saw in Ioan Vodă a forerunner of agrarian reform and of the “modern” state – a kind of Dacian and Trajan of Moldavian democratic ideals (albeit without a real Daco-Roman foundation, but rather inspired by Western and Byzantine models). The heroes of that time claimed that his bronze coins (sângiuri de aramă) and his fighter’s stance were a spark of national rebirth. However, the concrete links to modern Romania come only through descent and memory: his son, Ștefan Surdul, became ruler in Muntenia (1591–1592), and his grandson, Ionașcu Potcoavă, briefly ruled in Moldavia (1592). More accurately, the image of Ioan Vodă was revived by Alexandru Ioan Cuza and, from time to time, by Romanian writers of the past century – in the modern struggle for unity and the rediscovery of Romanian identity.

Today, in an age of populism and occasional nationalist hysteria, some might go so far as to grotesquely force the idea of Romanian continuity, trying to link the deeds of Ioan Vodă to a contemporary figure like Ciolacu – but that would be like comparing a fallen lion in battle to a fat fly sighing lazily among spoons of honey and taxes. Others, driven by well-channeled ultra-nationalist fervor “imported from elsewhere,” like Simion or Georgescu, would assign him mystical missions and Dacian blood in his veins, entirely ignoring the fact that nearly 2,000 years have passed since the conquest of Dacia. In truth, Romanian imagination has dressed Ioan Vodă’s history in the wide sash of historical continuity, but the fact remains: Ioan’s first true emblem is that of the “brave Romanian,” not that of a “guardian of Dacia.”

🧠 Under the Lens of Propaganda: How Events Were Rewritten for Ideological Agendas

The figure of Ioan Vodă has passed through multiple filters of propaganda and myth-making over the decades. During the Phanariot era, the boyars of the 18th century remembered with dread the "Armeanul" (the Armenian), the harsh ruler who had disrupted the comfort of their privileges. After 1859, however, nationalist historians reshaped his image. Writers such as Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu portrayed him—in his 1865 “monograph,” Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit (Ioan Vodă the Terrible)—as a visionary of social justice, a sort of pre-Cuza spirit of fairness. His courage in confronting the boyars was seen as proof that the Romanian spirit was compatible with reform—an idea extremely popular among the staunch supporters of Cuza’s agrarian reforms. Later, the communist leaders of the 1950s reclaimed the legend of Ioan Vodă in a new light: emphasizing his ties to the Cossacks—friends of the peasants—in order to suggest that Moldova had historically been "a progressive homeland, prepared for the international cooperation of working peoples."

Religion also played a sporadic role. The Orthodox Church, though weakened at the time, did not support Ioan Vodă—he burned bishops and struck at monasteries. The communist regime later amplified his anti-religious image; both the communists and later nationalists labeled the faithful as “bearded boyars,” noting that Golia, Petru Șchiopul, and the other “traitors” were, in fact, secularized priests—a form of ideological intimidation reminiscent of the atmosphere in The Apocalypse with the Duke and the Camels. Today, some ultranationalists still circulate outlandish rumors: that Ioan Vodă "cursed the boyars" in his final moments, or that hidden treasures are waiting to be found. These are, however, nothing more than modern fables—there is no serious historical evidence to support prophecies or supernatural scenarios.

In reality, propaganda shaped the image of Ioan as suited the needs of each era. Communism portrayed him as a kind of “strong man of the people,” while the 19th century painted him as a “romantic nationalist.” Meanwhile, English and Polish archives mention even the gruesome or painted details of the Turkish tortures (foreign eyewitnesses recounted decapitations and binding between camels), yet Romanian propaganda ignored such horrors. Similarly, right-wing parties excelled at highlighting the Christian suffering of a “martyred Romania” standing up to Turkish power (insisting on the image of his crushed head), while left-wing parties emphasized his acts of social justice—conveniently forgetting the tragic outcome. Honest information never aligns with vulgar political exploitation: this is why the present project takes on an educational role, explaining that Ioan Vodă was both—a military visionary who modernized Moldova and a harsh ruler, but also a man who suffered an atrocious death.

⛪ Shadows on Icons: The Absence of a Fighting Church

As for the Church, it mostly stood in the shadows or in the corner of popular joy. Ioan Vodă, secular in conviction, had nothing to do with ecclesiastical leadership in his fight for independence. On the contrary, the years 1572–1574 were a nightmare for the surviving clergy: the boyars, astonished that God did not truly become angry when Ioan burned bishops, were rather trying to understand why this otherwise respectable man was confiscating their properties—not why he was “burning grace and bread.” (A subtle jab, of course, since priests had come to collect the bread of the boyars, not the people.) In the chapter on “historical truths,” we will plainly state what position the Church held—if it truly held any at all. After all, in Jerusalem there were cases when patriarchs cursed kings, and in Rome religion was a form of power. But in Suceava or Iași in the 16th century, the only concrete role of religion was to occasionally offer a patch of land where Ioan might pray or lay down a tribute of arms (the holy cross, for example, on which Golia swore “not to betray”). No old monk ever changed the course of battle. Here, “high” politics still took place in the attic of the treasury, and the Holy Spirit was probably too busy chasing stars through cannon steam. That is why we will not dedicate an entire chapter to Ioan Vodă’s Church, but instead will mention a few facts in the context of struggle and consequence—showing that the real politics of the age were secular and cruel.

🪞 “Hero” or “Monster”: Symbols, Allegories, and Historical Parallels

In our narrative, two powerful symbols have already echoed: the Allegorical Cossack and the Cursed Cannon. The White Cossack – his military companion – becomes a modern symbol, a living tableau through which the Moldavian, clad in feathered uniforms, remains by his side. Heavy artillery also stood as a symbol of the age: the image of the Moldavian who, like a rudimentary Daedalus, shapes the bowtie of a war train (the cannons!) only to become, tragically, the apprentice to his own Icarian fall. The politics of cannons and sacrifice evokes the myth of the drowned soldier at Gallipoli or the atmosphere of the Drum bun march, echoed as well in the Romanian film For the Fatherland (Pentru patrie, 1978). It may sound strange, but the way the Ottoman breaks his pact with the ruler brings to mind any “promise broken by power.”

We will sprinkle analogies and a parable: for instance, the reign of Ioan Vodă resembles a version of The Flight of the Locust: a fearless character (much like Romanian programmers born under communism, in a way) who steps forward to “move mountains,” only to be torn apart by external partners for his boldness. (Or, to avoid quoting modern jargon directly, imagine cinematic scenes with mad commanders: what would a Pacino look like on the Roscani embankment?) Notably, June 14 remains a fateful date on the calendar: on one hand, it marks the battles of Ioan Vodă, and on the other, it connects to other decisive confrontations – from Marengo (1800, Napoleon overpowering Austria) to the adoption of the tricolor flag (1848). We won’t claim that history linked them intentionally, but we certainly emphasize the brutal rule of 1574 within a broader context: yet another sign that the history defining us is full of late victories and chilled defeats – and the legend of Ioan Vodă fits among them precisely like a war icon burning brighter than the city-bound achievements of the age.

To bring in the touch of humor we like, here’s a joke for the younger ones (or for those who forgot their school lessons): “The two Jeremiahs – meaning Ieremia the Armenian and Ieremia Golia – might just be the most famous Jeremiahs in Moldavian history! One was a chronicler and scholar (Ieremia Golescu, considered the first modern Moldavian chronicler, from an Armenian family), and the other – a notorious traitor in the service of the Ottoman Empire. Their only common point? They both started with Ierem- and ended up under a canopy, but their fates were completely different. Eh, let’s not drag Ioan Vodă the Armenian into this wordplay too, or it’ll become a story too long!” This play on clever names is our way of reminding readers that even historical conflicts hide “coded” words – and we’ll try to decipher them all, like cousins of erudition.

🎲 Trivia and Historical Humor

- Did you know that... Ioan Vodă used to sign his official documents as "Ioan Vodă, son of Ștefan Voivode"? In other words, he put down on paper a noble little fib: that he was the legitimate son of Ștefăniță (son of Ștefan cel Mare) – when in fact, he was a bastard! (At the time, this official announcement fooled nearly all his enemies. And the boyars? Well, they were probably less outraged by the lie itself... and more by the boldness with which it was written on a state diploma!)

- Parabolic and devilishly military: imagine if Ioan Vodă had a marketing advisor like leaders do today. He would probably have branded his reign as the military campaign “#MoldaviaFights,” and his conquest mission would’ve instantly gone trending. One thing’s for sure: after arming himself with two hundred cannons, he could be seen as a sort of “godfather of Eastern artillery” (not by chance was he compared to his European forebears, those who laid down “powder and shadows” on the battlefields).

- Language curiosity: the nickname “the Terrible” stuck to him like a historical Coca-Cola label – the boyars branded him that way out of revenge, frightened by the pelivan and mace that were no longer just for show. At first, they only wanted to throw him into the “slammer” (as their power tantrums would go), but later they found a way to repackage him as a kind of superhero: some say today that “the spirit of the Terrible was actually terribly good for the peasantry.” Ha! That’s history for you: for four centuries, people have kept claiming “this ruler was misunderstood, the hero Romanians were looking for” – even though his medieval portraits kept rolling between fear and admiration.

- Military trivia: Generals around the world would probably love to know that Ioan Vodă’s Moldavian army had a rare innovation for its time: light cannons pulled by just two horses – a kind of “mobile artillery workshop” back then! Even the great commanders of Renaissance Europe didn’t enjoy that kind of mobility. This was, in fact, one of his key advantages in fighting the Turks: some historians say he managed to hold out for hours precisely because he didn’t abandon his cannons. There’s even talk of a lucky break (maybe the weather, maybe a delay on the enemy’s part) that saved part of his troops. Instead of fleeing, they retreated with their shells in tow – like true knights of Moldavian fire.

👉 Even Napoleon would’ve raised an eyebrow if he had seen something like that in Moldova back in 1574! - Everyday detail: Iași was just a small, dusty market town when Ioan Vodă decided to make it the capital. The city, with its moldy ditches and muddy alleys, was suddenly given the title of a “visual fortress.” Naturally, the boyars grumbled that he didn’t know how to “sell” the city’s image the way they would have. To all the whining, Ioan would’ve likely replied bluntly: “If I hadn’t made Iași the capital, we’d still be sitting around like fools in Suceava, in some cart!” And ironically, two centuries later, Moldavians were still sitting around like fools – in the same Iași, now with a pavilion replica in the center of the city. (Meaning a modest princely building inspired by the old Suceava palace, but lacking its former splendor: a capital in name only, more like a stage prop.)

- Curious irony: Later on, the reporters of the time (Polish, German, and Italian chroniclers) referred to Ioan as “the boyars’ ignorant voivode” — yet even they had to acknowledge his strength of character. A Pole from Kraków wrote that “the true chronicle of the battle in Moldavia” reveals one key fact: Ioan was a proper military man, who fought like a hurricane, and was brought down only because of a lowly Betrayal — with a capital “B.”

And now, honestly: if there had been a review system back then like today's online ratings, both treacherous parrots — Petru Schiopul (the boyar backed by the Ottomans) and Golia (the Moldavian captain who switched sides) — would have earned a well-deserved score of zero stars for “dereliction of duty” or “loyalty.” They might’ve even gotten a warning label: “Caution: prone to betrayal without notice!”

Epilogue: Ashes and Iron

This land has never rested under the footsteps of history. It has been crucified, sold out, choked by betrayals, and scorched by taxes. But sometimes, from blood-soaked soil, iron has risen. And from iron, will. And from will, people.

In a century when thrones were traded like herds and the sword was the language of diplomacy, one name pierces through the dusty pages of history with brutal force, impossible to ignore: Ioan Vodă the Brave. Not a saint. Not a chancery noble. Not a Phanariote anointed with Byzantine myrrh. But a man born in shadow and dead in flames, whose bones were crushed not only by Ottoman blades, but by his own people.

We teach him as a hero. Or we forget him. Or we blame him. Or we place him on gold coins that have lost their value. But Ioan Vodă does not fit into any mold. He was too harsh for the boyars, too poor for crowns, too free for the Ottomans, and too early for a people who still didn’t know what freedom meant. A son of Moldavia who came not to reign, but to take revenge. On history. On traitors. On injustice.

He thrust his sword into the face of an empire and demanded answers from those who sold the land like a dowry. He raised an army from the mud and led it, in rags and banners, against the greatest power in the world. He was betrayed not by enemies, but by his own. And he met his death not in battle, but by boiling. Literally.

This is not a story with a happy ending. It is not a fairy tale. It is a wound from history that has yet to heal. A testimony to how hard it is for iron to rise from the dust – and how quickly it is buried again by forgetfulness.

The last gaze of iron before it was buried beneath ash. Ioan Vodă – not an icon, but a living wound in the history of Moldavia.

The last gaze of iron before it was buried beneath ash. Ioan Vodă – not an icon, but a living wound in the history of Moldavia.

📖 Glossary of Terms and Concepts

- Voievode/Ruler: The official title of the leader of a land such as Moldavia or Wallachia, equivalent to "prince" in medieval Europe. Although Ioan Vodă was an illegitimate son, he was nonetheless named Voievode of Moldavia through the vote of the boyars and with the sultan’s approval – as required by the political customs of the time.

- Sultan: The supreme ruler of the Ottoman Empire. Moldavia was a vassal state, and its ruler needed the sultan’s confirmation to be officially recognized. Ioan Vodă was approved by the sultan, but ultimately rebelled against him.

- Vassal / Vassalage: A relationship of subordination to a more powerful state. Moldavia was a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, paying tribute and accepting certain conditions, although braver rulers (like Ioan Vodă) occasionally tried to break free from this domination.

- Ottoman Armies: A complex military structure composed of janissaries (elite infantry), sipahis (cavalry), Crimean Tatars, volunteers, and mercenaries from various provinces. In the campaign against Ioan Vodă, the Ottoman and allied forces likely exceeded 80,000 troops—some sources even report over 100,000—which highlights the massive imbalance of power.

- Janissary/Janissaries: The Sultan’s elite soldiers, considered invincible at the time. Despite their fearsome reputation, they were defeated in several battles by Ioan Vodă, thanks to his ingenious tactics and skillful use of the terrain.

- Spahis (including the Ottoman cavalry): Elite Ottoman cavalry composed of mounted soldiers who were granted land (called timar) in exchange for military service. The spahis were a core component of the Ottoman army, playing key roles in battles, especially on open terrain. They were equipped with swords, lances, and bows, and were known for their discipline and mobility. In the campaign against Ioan Vodă, the spahis fought alongside the Janissaries, Tatars, and other Ottoman forces.

- Tatars: A nomadic people of Turkic origin, often allied with the Ottomans. During his campaigns, Ioan Vodă frequently faced devastating Tatar incursions. The Crimean Tatars were involved in raids, looting, and battles as part of punitive expeditions in Moldova.

- Boyar: A high-ranking noble, usually owning vast estates and wielding significant influence in the governance of the country. In Moldova, boyars often held the real power and much of the wealth. They called Ioan Vodă “the Terrible” because he confiscated the lands of traitorous nobles and punished them harshly.

- Boyar Betrayal: The act by which boyars conspired against the ruler, often to preserve their privileges or out of personal interest. It was one of the main challenges Ioan Vodă faced during his reign.

- Divan: The official assembly of boyars in Moldavia, where important decisions were made, including the election of the ruler. Ioan Vodă was appointed as prince with the support of the Divan, even though his illegitimate origin would normally have been a major obstacle.

- Hatman / Hatman of Moldavia: A significant military title in medieval Moldavia, equivalent to a commander-in-chief, particularly of the cavalry. Ieremia Golia, Ioan Vodă’s hatman, was one of the most important military leaders of the time. His betrayal—when he switched sides and joined the Ottomans during the Battle of Ierzerul Cahul—was a decisive moment that led to the prince’s defeat.

- Chronicler: A medieval historian who recorded the events of the time. In the case of Ioan Vodă, sources such as Marcin Bielski, as well as Ottoman and Moldavian chroniclers, left us direct accounts of his reign.

- Short reign: An expression describing the relatively brief period (1572–1574) during which Ioan Vodă ruled Moldova, yet one that had a disproportionately large impact on national history and memory.

- Feudalism: A social and economic system in which the ruler granted estates to nobles (boieri) in exchange for loyalty and service. Moldova followed this structure, but Ioan Vodă sought to curb the abuses of the nobility.

- Lower Country / Upper Country: The traditional geographic-administrative divisions of medieval Moldavia. The Lower Country referred to the southeastern region (including Galați and Cetatea Albă), while the Upper Country encompassed the northern area (such as Suceava and Hotin). Ioan Vodă’s military campaigns focused especially on defending the Lower Country.

- Tighina, Cetatea Albă: Key fortresses of Moldavia in the southern region, located near the Danube and the Black Sea. Tighina (now Bender, in Transnistria) and Cetatea Albă (now Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, in Ukraine) were vital strategic points for the country’s defense. In 1573, Ioan Vodă achieved several victories against the Ottomans and Tatars in these locations, temporarily strengthening Moldavia’s control over the area.

- Raya (raia): A Moldavian territory placed under direct Ottoman administration (e.g., Tighina became an Ottoman raya after Ioan Vodă’s death). Such regions were often ceded as a result of military defeats or political betrayals.

- Cossacks (Zaporozhian Cossacks): Warriors from the southern steppes of present-day Ukraine, known in the 16th century for their bravery and skill in fighting the Ottomans. Ioan Vodă called upon a contingent of Cossacks to aid Moldova, relying on their discipline and experience with firearms.

- Pârcălab: The governor of a fortress, responsible for its defense and administration on behalf of the ruler. Ieremia Golia was appointed by Ioan Vodă as pârcălab of Hotin, but it was there that he is said to have accepted a bribe from Petru Șchiopul and ultimately betrayed his lord by abandoning his cause.

- Mucarer (mocorier): A fiscal official introduced in Moldavia after 1574, responsible for collecting taxes and tracking down those who evaded payment. Although the position was not directly established by Ioan Vodă, his harsh tax policies and crackdown on fiscal evasion helped lay the groundwork for its later creation.

- The Turkified (Turcitul): A nickname—often used pejoratively—for individuals who converted to Islam or sided with the Ottoman Empire. In Moldavia, there were rumors that Ioan the Brave (the illegitimate son of Ștefăniță Vodă) had once lived among Muslims, possibly even converting temporarily, though he returned to Christianity before becoming ruler of Moldavia.

- Axe (symbolic): A symbol of the punishments imposed by Ioan Vodă on treacherous boyars. He is often depicted holding an axe, representing his harsh justice and ruthless authority.

- Execution by quartering: An extreme form of punishment reserved for leaders who defied the Ottoman Empire. Ioan Vodă was quartered by camels — a brutal death meant to instill fear and enforce submission.

- Cruel End: Romanian, Polish, and Ottoman historical sources record that Ioan Vodă suffered an extremely violent execution: he was first stabbed in the neck, then tied to four camels that pulled in opposite directions until his body was torn apart. The Ottoman executioners collected pieces of his body as trophies or talismans. This form of torture had a symbolic purpose and was reserved for leaders who offered fierce resistance. The Polish chronicler Marcin Bielski and contemporary Ottoman reports confirm this episode.

📚 Historical References

- Manea, Irina-Maria, „Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit, un personaj unic în istoria românească”, în Historia (portret istoric), 2013.

- Dumitrescu, Ionel-Claudiu, „Moartea lui Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit: sfârșitul în trădare și sânge al Moldovei eroice”, în Historia (article general), 2016.

- Pătrașcu Zamfirache, Cosmin, „Voievodul exotic din istoria românilor. Ioan Vodă cel Viteaz”, Adevărul (studiu editorial), 18 aprilie 2023.

- Mica istorie: 14 iunie – ziua când tricolorul a devenit steagul României, spotmedia.ro, 2024 (secțiunea despre 1574 și Ioan Vodă).

- Ziarul de Vrancea, „Ion Vodă cel Viteaz – un geniu militar vizionar”, 14 iun. 2024.

- Istoria lui Ioan Vodă în cronici medievale: Paprocki, „Adevărata descriere a războiului…” (Cracovia, 1575) și Leonhard Gorcki, „Descrierea războiului purtat de Ion domnul Moldovei cu Selim” (Frankfurt 1578). (Menționate în Arhiepiscopia Sucevei 2022).

- Xenopol, Alexandru D., Istoria românilor din Dacia Traiană, vol. V (București, 1925), p. 86-107 (originile familiei și introducerea mucarerului) – cit. în surse moderne.

- Giurescu, Constantin C., Istoria românilor, vol. III (București, 1946), pp. 462–463 (politica lui Ioan Vodă, suprimarea boierilor şi clerului).

- Paprocki, Bartholomaeus (Bartolomeu), Druga część opisania wojny tureckiej (Cracovia, 1575) – cf. Istoricul Apostol Stan.

- Bielski, Marcin (Martin), Chromna Polonicae historiae (Cracovia, 1591) – cronică poloneză despre ocupația moldovenească și uciderea lui Ioan.

- Ureche, Grigore, Letopisețul Țării Moldovei (secolul al XVII-lea, ed. Gh. Asachi).

- Costin, Nicolae, Letopisețul Țării Moldovei (secolul al XVII-lea).

- Hasdeu, Bogdan P., Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit (monografie, 1865).

- Giurescu, Dinu C., Ioan Vodă cel Viteaz (monografie, 1974).

- Rezachevici, Constantin, Cronologia critică a domniilor din Țara Românească și Moldova, 2015.

- Surse adiacente: Ziarul de Alexandria (Adevărul), „Cumplita moarte a domnitorului Ioan Vodă cel Viteaz” (2016); concizări din portale istorice românești şi europene indicate mai sus.

Citations:

- Moartea lui Ion Vodă cel Cumplit: sfârșitul în trădare și sânge al Moldovei eroice

- Astăzi despre: Ion Vodă cel Viteaz | Un geniu militar vizionar. Domnitorul care a anticipat importanța artileriei.

- Ioan Vodă cel Viteaz - Wikipedia

- Cumplita moarte a domnitorului Ioan Vodă cel Viteaz: turcii i-au tăiat capul, i-au sfârtecat trupul în patru şi au păstrat bucăţi de carne ca talismane

- Ieremia Golia - Wikipedia

- Ion Vodă cel Viteaz – domn al Ţării Moldovei – Arhiepiscopia Sucevei și Rădăuților

- Ioan Vodă cel Cumplit, un personaj unic în istoria românească

- Voievodul exotic din istoria românilor. Ioan Vodă a fost „cel viteaz“ sau „cel cumplit“ | adevarul.ro

- Mica istorie: 14 iunie - Ziua când tricolorul a devenit steagul României - spotmedia.ro

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0