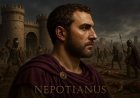

The Gladiator Emperor: Nepotianus and the Last Breath of Constantinian Rome

In June 350 CE, Nepotianus—nephew of Constantine the Great—stormed Rome with a gang of gladiators and seized the throne. For 28 brutal days, he ruled amid street violence, dynastic chaos, and civil war—before being crushed and paraded dead through the streets. This gripping deep dive unravels the rise and fall of the “Gladiator Emperor” in a tale of ambition, bloodshed, and the crumbling Roman Empire.

Crown of Gladiators: The Short Reign of Emperor Nepotianus

A Nephew’s Gambit: Shadows over Imperial Rome (Introduction)

In the summer of 350 CE, the Eternal City bore witness to a bizarre and tragic power grab. A little-known aristocrat, Flavius Popilius Nepotianus – the nephew (Latin nepos) of the great Emperor Constantine – suddenly appeared at Rome’s gates at the head of a ragtag band of gladiators (probably a few hundred), demanding the purple throne. Imagine the scene: gladiators in armor, not in the arena but in the Forum, cheering on their new emperor. For Rome’s citizens, this must have felt like a nightmare from the past – a reminder of lawless violence invading sacred precincts.

This startling revolt was more than just another usurpation; it was a desperate clash of ambition, loyalty, and violence. On one level it reflects the chaos of a fractured empire: Nepotianus was a surviving member of Constantine’s family (hence his name) trying to reclaim power amid civil war. On another level, it has an almost cinematic quality: gladiators turning arena fights into real warfare, a grand nephew usurping imperial garb, and ultimately a savage end. As one ancient chronicler put it, Nepotianus “was cut off on the twenty-eighth day of his usurpation… his head was carried through the city on a lance”. His brief story is a footnote to history – but a vivid and cautionary one, showing how quickly fortunes can change.

An Empire in Turmoil: Context and Causes

To understand why Nepotianus dared to revolt, we must first see Rome’s larger crisis in 350 CE. Just months before, a powerful soldier named Magnentius had rebelled in Gaul, assassinated Emperor Constans (Constantine’s son) in January 350, and seized control of Italy and the Western provinces. This sudden coup left Italy ruled by a usurper, so Constantine’s dynasty (the Constantinian family) was suddenly leaderless in the West. Meanwhile, in the Balkans a veteran general named Vetranio was proclaimed emperor by Illyrian troops in March 350. The Roman world was basically split among Constantius II (in the East), Magnentius (West), and now another claimant, Vetranio.

In this chaotic power vacuum, Nepotianus saw an opportunity. He belonged to the Constantinian dynasty – his mother Eutropia was Constantine’s half-sister and his father, Virius Nepotianus, had been consul under Constantine. In an empire where “the purple” (the imperial title) often passed by blood or force, Nepotianus had some claim by lineage. Moreover, with Magnentius occupied in Gaul and Italy under his command, Nepotianus may have reasoned that Rome itself was lightly defended. Indeed, one source notes that while Magnentius was in Gaul, Nepotianus “collected a band” of men and marched on Rome. These men are described as “persons addicted to robbery and all kinds of debauchery” – essentially a mob of unruly gladiators and outlaws ready for a fight.

In short, the causes of Nepotianus’s revolt included the dynastic crisis (Magnentius’s coup against the Constantinian line), the power vacuum and unrest in Italy, and Nepotianus’s own imperial ambitions and family ties. It was a desperate gamble: a Constantinian nephew betting on a split empire and using Rome’s own entertainers (gladiators) as shock troops.

The Gladiators’ Charge: Nepotianus Takes Rome

On 3 June 350 CE, Nepotianus made his move. He entered the city “in an imperial dress” at the head of his grim procession. The city-prefect (the urban praetor, often called the Praefectus Urbi) at the time was a man named Anicetus (also called Titianus or Anicius in sources). He attempted to defend Rome by arming a crowd of civilian volunteers, but the hastily-levied Romans could not stand up to Nepotianus’s fighters. According to the chronicler Zosimus, a “sharp conflict ensued”: the undisciplined Roman force broke ranks under the onslaught, and Anicetus hastily shut the city gates in panic. In the chaos, Nepotianus’s gladiators hunted down the fleeing defenders outside the walls, killing every man they caught.

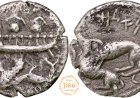

With the prefect’s levies routed, control of the city passed to Nepotianus almost effortlessly. Within days, he had himself acclaimed Augustus (emperor) by the remaining guards and populace. Ancient sources tersely note that Nepotianus “took the name Augustus” upon the throne. He even had coins struck in his name (some rare bronze coins survive), putting his face and the title CAES(AR) on them – symbolic assertions of his new status. For nearly four weeks, Rome was in his hands.

We can only imagine what those days felt like for Nepotianus and for ordinary Romans. For Nepotianus, it must have been a heady moment: the purple robe on his shoulders, senators swearing loyalty, and the cheers of gladiators who saw him as a heroic liberator. For fearful citizens, it was a nightmare of violence and uncertainty. The usual order of daily life was shattered: shops closed, the forum emptied, and anyone thought loyal to Magnentius or the old regime might have gone into hiding. (Fact: Ancient authors do not describe much more about what he did, only that he held Rome for 28 days.)

All the while, one fact loomed: Magnentius had a powerful army and would not ignore this challenge. In the final week of June, Nepotianus’s supporters must have realized that help was coming.

The Fall and Aftermath: Immediate and Long-term Consequences

The uprising collapsed almost as quickly as it began. Magnentius, furious at the news, sent his trusted general Marcellinus with troops from the Rhine to recover Italy. In the last days of June 350, Marcellinus marched on Rome. In a brief counterattack, Nepotianus was overwhelmed. The ancient historians agree: Nepotianus was put to death by Marcellinus’s forces. One vivid account from Eutropius emphasizes the grisly end: Nepotianus “was cut off on the twenty-eighth day of his usurpation… his head was carried through the city on a lance”. Even after his death, his revolt left bitter traces: days of proscriptions ensued, and many of his supporters – including, reportedly, his mother Eutropia – were executed in the city.

In practical terms, Magnentius had immediately regained control of Rome and Italy. Nepotianus’s short-lived empire vanished in days, but not without cost: Rome’s streets were bloodied, and many nobles were purged, creating grudges and grief in the senatorial class. For Magnentius, the revolt was an unwelcome distraction just as he was preparing to face the Eastern Emperor Constantius II. (Modern historians note that it likely delayed Magnentius’s plans by a few weeks.) Nonetheless, Magnentius eventually regrouped, but his overall campaign ended in disaster: at the Battle of Mursa Major (September 351) he was defeated by Constantius’s forces, and by 353 he took his own life to avoid capture. In effect, the empire soon reunited under Constantius II. Nepotianus’s brief episode faded from immediate consequence: he had no successor and left no lasting reforms or movements behind.

Long-term, Nepotianus’s revolt is remembered only as a curious footnote. It showed how extreme the Constantinian succession crisis had become, but it did not change the sweep of events. Later Roman historians (like Ammianus Marcellinus) barely mention it. In fact, except in specialized studies, few ancient accounts focus on Nepotianus at all. Modern scholarship likewise treats him as a minor player: for example, Shawn Caza notes that all sources agree only on two things about Nepotianus – he rose after Vetranio in March 350 and before Mursa in September 351, and he “had a very short reign and was defeated”. In that sense, his revolt left no new dynasty or ideology; it merely underscored the empire’s fragility. As one modern survey puts it, Magnentius “crushed Nepotianus” in June 350, then moved on.

Historians and Hearsay: Interpretations Then and Now

How should we interpret Nepotianus’s strange bid for power? Ancient authors offer a consistent, if biased, picture: they present Nepotianus’s revolt as a foolish and “savage” attempt that was brutally quashed. Eutropius, writing under the later emperors, condemns the uprising in moral terms: he says Nepotianus’s “savage attempts merited” the fate of execution. Zosimus, writing a century later, describes Nepotianus’s followers as “persons addicted to robbery and all kinds of debauchery”, painting the revolt as the work of criminals rather than patriots. These slanted portrayals are historical facts (the exact words of our sources), but they also reveal bias: they serve to justify Magnentius (and ultimately Constantius) as restorers of order.

Modern scholars note this bias and try to read “between the lines.” (Analysis: None of these sources gives Nepotianus any credit or rationale; he’s simply a villain.) For example, when Eutropius calls the 28-day revolt “savage,” we should recognize that he is writing for the victors in Constantius’s court. Today, historians ask whether Nepotianus had any real chance or support, or whether he was acting as a puppet for other discontented nobles. They also examine small details that conflict: some accounts imply the city prefect Anicetus fled into hiding, while other evidence suggests he might have died fighting. In one modern analysis, discrepancies in the timeline have led scholars to question whether the accepted dates (3–30 June 350) are correct.

Thus, “interpretations” of Nepotianus vary. Some see him as an opportunist, seizing a crisis out of personal ambition. Others imagine a more sympathetic picture: perhaps he was a last-hope figure for the old Constantinian aristocracy. Because surviving sources are brief and partial, much is conjecture. (Interpretation: Given his familial ties, it’s logical Nepotianus might have felt he had a legitimate claim, even if many Romans disagreed.) Importantly, modern analysis always distinguishes what ancient texts say (facts) from what we infer (commentary). In this case, the clear fact is that Nepotianus was swiftly defeated and died; everything else – his motives, the people who helped him, even the exact timing – is pieced together by historians who must read the lean sources critically.

Spin and Stonewall: Nepotianus in Propaganda and Myth

Almost immediately, Nepotianus’s rebellion became part of imperial propaganda. Official accounts in Constantinople and the court of Constantius II had little interest in a brief Western pretender, but they did emphasize Magnentius’s victory. Magnentius himself, when defending his rule, portrayed Nepotianus as a usurper whose execution proved his own legitimacy. Indeed, Magnentius took pains to curry favor with the Roman Senate after Nepotianus’s fall (revoking Constantine’s ban on certain pagan rites to please the Romans). Thus, the message was: Magnentius quelled this disorder, whereas those who backed the Constantinian cause (like Nepotianus) got swept away.

Later chroniclers leaned into this narrative. In history texts, Nepotianus is either a footnote or a villain. For instance, the Epitome de Caesaribus tersely notes: “Nepotianus… took the name Augustus; Magnentius crushed him in twenty-eight days”. (Fact: This is exactly what it says.) And indeed modern summaries often echo that phrasing. The brutality of his end – a head on a spear – was remembered more as a warning than as martyrdom. In this way, Nepotianus’s story was used ideologically to show the dangers of illegitimate power. (Interpretation: It’s telling that no source valorizes Nepotianus or even names him without disdain.)

Even in modern times, Nepotianus often appears only in the context of Magnentius’s career. Encyclopaedia entries, for example, mention him just to note Magnentius “crushed Nepotianus” before moving on. The enduring propaganda is subtle: because all surviving sources come from the winning side, we see Nepotianus only as a doomed rebel. In short, his story was quickly spun into the narrative Magnentius and Constantius wanted: a brief, doomed insurrection that justified their iron control.

Church and State: The (Non-)Role of Religion

By 350 CE, the Christian Church was already influential in Roman politics, but in Nepotianus’s revolt it played no visible role. We have no record of any bishop or theological dispute connected to the events in Rome that June. Unlike some other civil wars of the era, this was not a quarrel of heresy or creed. Nepotianus himself was likely a Christian (as his Constantinian relatives were), but he did not campaign on any religious platform. Neither did Magnentius use religious slogans to rally troops against him (in fact, both Constantinian and Magnentian sides had Christians, albeit often Arians, involved). In short, everything in the sources points to a purely secular power struggle: an aristocrat grabbing power by force, and a rival usurper crushing him for it. The Church’s great controversies of the 4th century (Arianism, councils, etc.) were unrelated to Nepotianus’s story.

Symbols and Parallels: Allegory and Irony

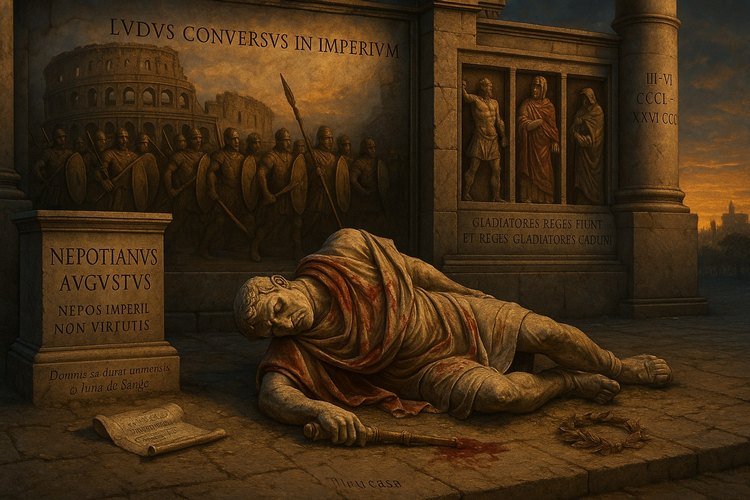

Although brief, Nepotianus’s uprising is rich with symbolism and echoes of other stories. The most obvious image is the gladiator band itself. In Roman culture the gladiator represents both violence and spectacle – to see gladiators marching through Rome wielding swords for a political cause was a stark reversal. Symbolically, it was as if Rome’s violent entertainment had come to devour its rulers. Some historians liken this to the earlier slave-turned-hero Spartacus: Spartacus once led gladiators in revolt against Rome (73 BCE), whereas Nepotianus – a man of the ruling class – hired gladiators to conquer Rome. It’s a curious parallel of role reversal.

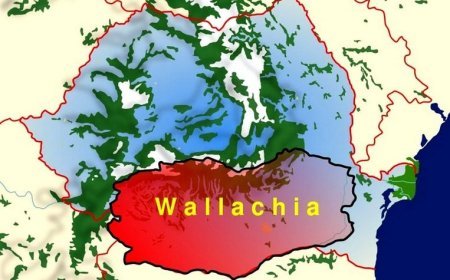

Another symbolic layer lies in the very name of Nepotianus. The Latin word nepos means “nephew,” and this root has been preserved in many modern languages. Particularly relevant is Romanian, a direct descendant of Latin, where nepot still means both “nephew” (the son of one’s sibling) and “grandson” (the son of one’s child), maintaining not only the form but also the familial connotations of the original term. This linguistic continuity is telling: it bridges antiquity and the present, revealing how concepts of kinship and privilege have endured across the centuries. From this same root comes the modern term nepotism, now widely used to describe favoritism toward relatives regardless of merit. In this light, Nepotianus’s name—essentially meaning “of the nephew”—becomes strikingly ironic. His only claim to power rested on his blood connection to Constantine the Great, making him, in a sense, the very embodiment of nepotism. By assuming the title of Augustus, he cloaked himself in imperial purple—the traditional symbol of dynastic legitimacy—but his robe was soon stained with blood. His reign, lasting just 28 days, has come to symbolize the fragility of power built solely on inherited status: a brilliant flash of ambition, extinguished almost as soon as it appeared.

Date-wise, nothing magical stands out about June 350 specifically; it was simply a moment of opportunity. But one might note a dark symmetry: Nepotianus seized power on June 3 and died on June 30 – effectively ruling for exactly one month. Historians might wink that his empire only lasted a Roman mensis, a tidy but tragic symmetry.

In later thought, Nepotianus’s fate has sometimes been compared to literary figures. For example, one could liken him to an ancient Macbeth: ambitious, a ruler by dubious means, then undone by forces he underestimated. Or one could see the image of a fallen “gladiator-emperor” as an allegory of fallen pride. These parallels are drawn by readers (not by ancient sources), but they help make sense of why this story still intrigues us: it reads like a classical tragedy condensed into one brutal page of history.

Beyond the Text: Trivia and Witty Asides

Though his reign was brief, Nepotianus has gifted history with more irony per syllable than many emperors who lasted decades. Here are a few gems...

- Name Game: Nepotianus’s story is steeped in irony. His name literally means “nephew”. In fact, he was so nepotistic that historians quip “he took nepotism to the purple.” The prince who never was became the poster-child for nepotism-gone-wrong!

- Gladiators at the Gates: Using gladiators as soldiers was an unusual choice (and one might say it backfired). A clever comment might be, “Nepotianus tried to make gladiators heroes of his coup – but turns out real warfare isn’t in their performance contract!”

- Imperial Coinage: During his 28 days Nepotianus struck bronze coins calling himself Augustus. (History geeks love that one rare coin.) It’s said he might have been better off minting a few extra soldiers instead, because having heads on coins didn’t do him much good. Literally.

- Short-Lived Emperor: His reign of 28 days invites comparisons. For example, if he had ruled the supermarket, he could have won “Best 28 Days of Shopping.” Or if Thomas Edison had Nepotianus as an assistant, he might have jokes about “short-lived bulbs.” Nepotianus’s reign was shorter than the shelf life of a novelty lightbulb – bright for a moment, then darkness.

- Mother Knows Worst: Nepotianus’s mother Eutropia met a grim fate soon after; historians dryly note she might have wished she had taught her boy better inheritance manners. One might wryly suggest Nepotianus should have called himself “Augustulus” (like a little emperor) instead of “Augustus,” since it might have saved some embarrassment.

- Last of the Gladiator Emperors: Technically, Nepotianus may hold a unique title – the last Roman leader to storm the city with actual gladiators. (Later “emperors” would rely on armies or political maneuvers, not arena fighters.)

These tidbits and wordplays help us remember Nepotianus: an emperor who came, saw a crowd of gladiators, and… (spoiler) didn’t quite conquer history.

Glossary of Terms

- Emperor (Augustus): The ruler of the Roman Empire. In later times, “Augustus” was the official title of a Roman emperor. Nepotianus proclaimed himself Augustus (emperor) during his revolt.

- Usurper: A person who seizes power without legal right. Nepotianus was a usurper because he claimed the imperial throne by force, not through a lawful succession.

- Dynasty (Constantinian): A ruling family. The Constantinian dynasty was the family of Emperor Constantine the Great. Nepotianus was part of it — his mother was Constantine’s sister.

- Gladiator: In ancient Rome, a fighter who entertained crowds by battling others or wild animals in an arena. Nepotianus assembled a band of gladiators (and similar fighters) to help take the city.

- Praefectus Urbi: The “Prefect of the City,” roughly equivalent to a mayor or chief magistrate. When Nepotianus marched on Rome, the praefectus urbi Anicetus (Titianus) tried to defend the city.

- Propaganda: Information or statements used to influence opinions. In this context, Roman emperors and historians used propaganda to portray Nepotianus as a villain (so that the “rightful” ruler seemed justified).

- Debauchery: Immoral behavior involving indulgence in sensual pleasures. Zosimus described Nepotianus’s followers as given to “debauchery,” meaning the revolt was full of vice and disorder. (Glossary note: in this text, it’s just how an ancient source described them.)

- Interpretation (Historical): A way of understanding or explaining past events. Scholars interpret the facts from sources; for example, they must interpret Nepotianus’s motives because the ancient writers do not explain them.

- Insurrection: A rebellion or uprising against authority. Nepotianus’s takeover of Rome was an insurrection against Magnentius’s rule.

- Consul: One of two annually elected chief magistrates in the Roman Republic and Empire. Nepotianus’s father had been a consul, a sign of their high status.

- Coinage: The system of coins used as money. Nepotianus minted coinage (bronze coins) declaring himself emperor, which is one piece of evidence historians use to study his revolt.

Historical References

This account is based on a combination of ancient sources and modern scholarship. Key ancient historians include Eutropius (4th century CE), who briefly mentions the revolt; Zosimus (6th century CE), who describes the battle involving gladiators; and the Epitome de Caesaribus (often attributed to Aurelius Victor, late 4th century), which records Nepotianus’s 28-day reign. Modern historians like Shawn Caza offer analysis of the chronology and broader context. We also consulted reliable summaries such as the Encyclopædia Britannica entry on Magnentius. All specific details in the text are drawn from these well-established academic and ancient sources.

Citations:

- Zosimus, New History. London: Green and Chaplin (1814). Book 2.

- Eutropius: Abridgement of Roman History, Book 10

- Magnentius | Usurper, Rebellion & Defeat | Britannica

- Vetranio and Nepotian | Historical Atlas of Europe (3 June 350) | Omniatlas

- KOINON: The International Journal of Classical Numismatic Studies, Volume I

- Zosimus, New History

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0