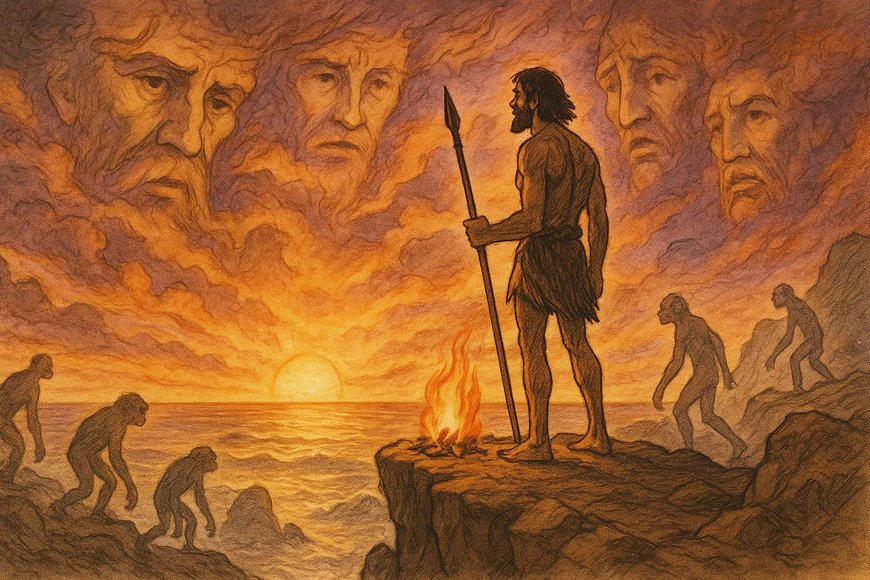

🜂 The Man Who Created His Gods

A critical and lucid analysis of religion, history, and human evolution. The manifesto reveals how humans created gods out of fear, how religion has controlled the masses, and how reason can liberate the consciousness. A non-religious essay, based on historical and scientific facts, about the origins of beliefs and their impact on civilization.

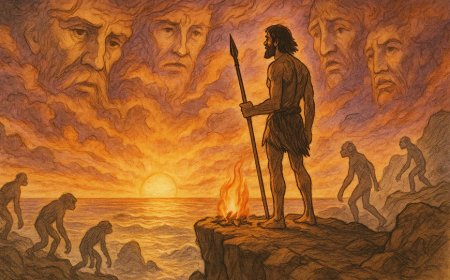

Humanity was not born from a divine will, but from a natural, slow, and relentless process: evolution. From inert matter, over billions of years, molecules capable of replicating appeared, then primitive forms of life, and finally complex species. Through natural selection, some organisms survived, others disappeared. Man, Homo sapiens, is the result of this biological chain, not the creation of any god. When I read Charles Darwin’s studies (The Descent of Man, 1871) and modern genetic research, I was fascinated to learn that Homo sapiens gradually evolved from primates, with a genetic similarity of 98–99% to chimpanzees (Chimpanzee Genome Sequencing Consortium, 2005). Discoveries such as the Lucy fossil, Australopithecus afarensis, dated to 3.2 million years ago, gave me a tangible picture of hominid evolution. Our ancestors were primates; from them evolved the hominids who raised their gaze to the sky, discovered fire, learned to speak, and acquired self-consciousness. When man realized he would die, fear arose. And from that fear, religion was born.

At first, religion was not theology, but an instinct. A primitive reaction to the unknown. Man began to see spirits in storms, gods in fire, souls in the wind, and meaning in death. Observing these phenomena and reading the works of anthropologist Edward Tylor (Primitive Culture, 1871), I realized that belief in spirits and invisible forces was a universal psychological reaction of humans. It was, for me, an attempt to symbolically control what could not be controlled in reality. Archaeological discoveries, including Paleolithic graves over 40,000 years old, showed me the existence of funerary rituals and belief in an afterlife. Thus myths, rituals, and the first beliefs were born. In small tribes, these ideas had a practical role: they provided moral rules, protected group cohesion, and imposed behaviors that prevented chaos. The concept of a “god who sees everything and punishes” seems to me the world’s first moral police.

When people formed large communities, leaders observed that fear of gods was stronger than any weapon. Thus, religion was transformed into a political instrument. Shamans, priests, and prophets, intermediaries between humans and deities, decided what was sin and what was virtue. Egyptian examples, with pharaohs proclaiming themselves gods, or Mesopotamian temples used as banks and administrative centers, clearly show how religion was used to control populations (Karen Armstrong, The Battle for God, 2000). In India and China, moral codes such as Hinduism, Confucianism, and Taoism had the same social and disciplinary function. In Judea, the idea of a single omnipotent god gave rise to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, religions that united millions of people, even by brute force, and imposed the greatest form of psychological domination documented historically. Documents and chronicles of the Crusades show how submission was often enforced through violence, fear, and manipulation (Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, 1951). Reflecting on these facts, I understood how fear was transformed into a tool of power and control, and how man created structures of authority around it.

Monotheistic religion imposed the “absolute truth,” a dogma that cannot be questioned. Religious leaders allied with political ones and established perfect order: power came “from God,” and submission was “man’s duty.” Under this system, crusades were waged, people were burned at the stake, continents were conquered, and genocides were justified, all “in the name of divine love.” In reality, it was for gold, land, and control. Researchers such as Henry Kamen (The Spanish Inquisition, 1997) clearly show how dogmas were used to control the masses and justify violence.

Over the centuries, religion has been the most effective form of collective manipulation. It provided simple answers to impossible questions, gave meaning to death through the promise of heaven, and enslaved the mind through fear of hell. It justified any violence as “divine will” and taught people that obedience is virtue, while doubt is sin. Those who used religion always lived well: protected, wealthy, and revered. Those who believed blindly in it were skinned, exploited, and kept in ignorance. This is the unwritten law of the world: those who use it live; those who follow it blindly pay.

In the European Middle Ages, the Church became the supreme power. It censored science, burned heretics, amassed huge wealth, and imposed fear as a governing tool. At the same time, it preserved writing, art, and education, not out of altruism, but to control information. The paradox is that the same religion that stopped knowledge prepared the Renaissance (unintended, but through much sacrifice, even blood, from scholars), which was to destroy it. This is documented by historians such as R. W. Southern (The Making of the Middle Ages, 1953).

When modern science emerged, mythical explanations collapsed one by one. It was shown that the Earth is not the center of the universe (Copernicus, 1543), that man is not made from clay (as evidenced by biology and paleontology), and that life was not created in a day (Darwin, On the Origin of Species, 1859). Biology, physics, and astronomy showed that the universe operates according to natural laws, without divine interventions. Faced with this evidence, religion retreated. The god with hands, anger, and judgment was replaced by a vague concept: “universal energy,” “cosmic consciousness,” “creative essence.” A modern reinterpretation, made so as not to contradict science directly. But this is no longer religion: it is poetic philosophy, a convenient rewrite, without empirical substance.

Viewed historically, religion has always been the same mechanism: invented to explain the unknown, organized to maintain order, exploited by elites for control, and transformed over time into cultural tradition. It did not liberate man, but kept him in fear, guilt, and obedience. Paradoxically, without religion, civilization would have developed the same, but without the pretext of fear that temporarily ordered the masses. Religion was both a chain and a ladder.

Even today, when humanity claims to have surpassed the age of dogmas, religion still influences politics, education, and public morality. In many states, laws are written according to sacred texts, not reason. Leaders invoke it to justify wars, to shape national identities, and to control votes. In place of the Inquisition, we have media manipulation; in place of burning at the stake, we have exclusion, shame, and social fear. There is even a desire to return to the past: a world easier to govern, where fear is again a political instrument and faith, a form of submission decorated with hope. Religion no longer wields the power of the sword, but it still wields the power of the mind, and that is perhaps the most dangerous of all.

Today, in the age of knowledge, dogmas survive not through evidence, but through man’s profound need for meaning, belonging, and hope. People do not believe in gods because there is evidence, but because they cannot face the existential void. Gods, angels, demons, miracles—all are mental projections, psychological reflexes through which man gives shape to the unknown and justifies his own good and evil.

The universe operates without gods; only man needs them to endure his own existence. Religion is not a discovery descending from heaven, but an invention raised from fear. It was created by humans to explain what they did not understand, used by power to control what could not otherwise be controlled, and perpetuated to give meaning to a world that otherwise seems inhospitable.

Science, evolution, and history show us clearly: there is no evidence for creators, angels, or demons, only for the natural process through which matter generated life, and life produced consciousness. What we call “God” or “Satan” are not beings of flesh and bone, but shadows of our own mind, reflections of human fear and hope.

This is the cold but liberating truth: man was not created in the image of any god; gods were created in the image of man. After researching and reading works by scholars such as Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion, 2006), Edward Tylor, Karen Armstrong, and Steven Runciman, I reached my own conclusion. My readings, observations, and personal reflections convinced me that gods did not create man, but humans created gods, in response to fear, the unknown, and the need for meaning. This is my understanding, built through experience, observation, history, and science.