11 May 330 – The Day Byzantium Became Constantinople: When a City Was Reborn as New Rome

On May 11, 330, Emperor Constantine officially inaugurated Constantinople as the new capital of the Roman Empire, transforming ancient Byzantium into the New Rome. Discover the origins of one of history’s most iconic cities.

Constantine’s Big Move: Byzantium Becomes New Rome

Chapter 1: A Greco-Roman Port with Two Seas

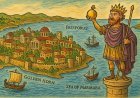

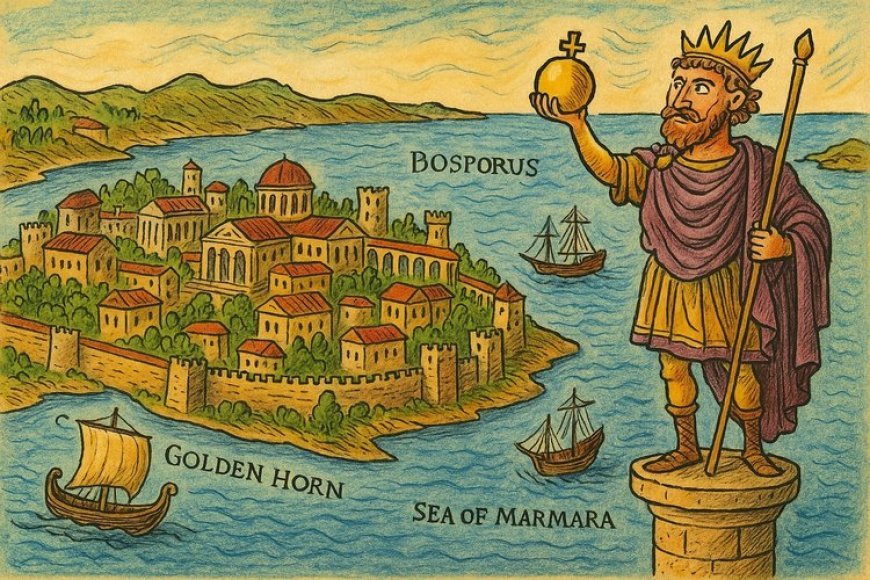

Long, long ago on the shores of the Bosporus there lay a sleepy little Greek town called Byzantium. Legend says it was founded about 657 BCE by a fellow named Byzas from Megara, which is why the city got its name (Byzantion in Greek). In any case, it was a real Greek city – colonists from Megara ran the place in the 7th century BCE – and it stayed mostly Greek-speaking all the way into Roman times. Byzantium was on a narrow peninsula with water on three sides (the Golden Horn inlet, the Bosporus Strait, and the Sea of Marmara), so ships from the Aegean, Black, and Mediterranean Seas all met there – not a bad spot for trade or defense. Even ancient writers noted that the site has seven hills, “requisite for Constantine’s ‘New Rome’”, just like old Rome did!

Byzantium wasn’t always the humble fishing village history remembers. In 196 CE, Emperor Septimius Severus razed the old town in a civil war and rebuilt it with grand new walls, even calling it “Augusta Antonina” after his son. (People apparently never got used to the fancy name, and it stuck in history mostly as Byzantium.) For most of its life up to then, Byzantium was a quiet backwater – until an ambitious emperor came calling.

Chapter 2: An Emperor with a Big Idea

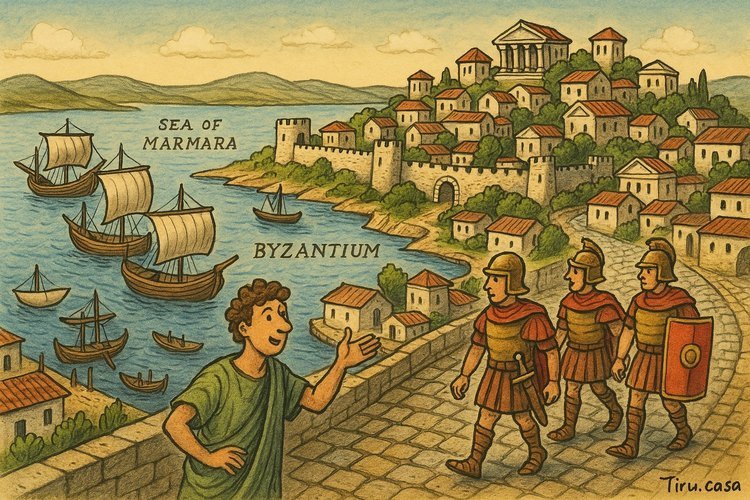

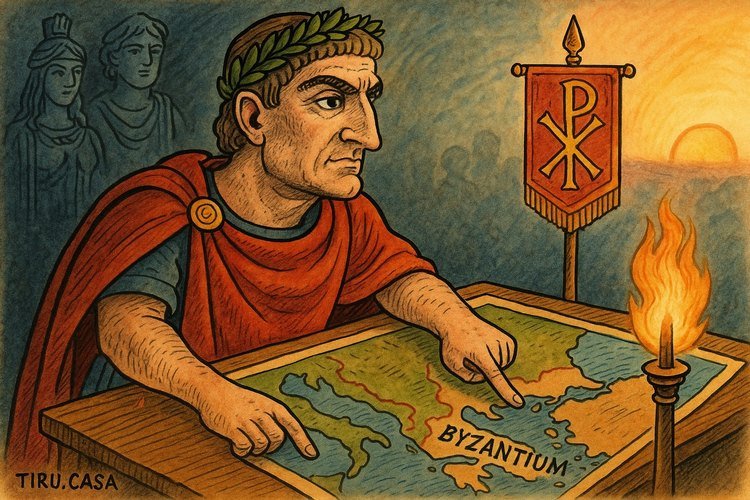

Fast-forward to the early 4th century AD. The Roman Empire had been split into East and West, but by 324 AD Constantine had won a string of epic battles (from Milvian Bridge to Chrysopolis) and reunited the empire under his sole rule. As one scholar puts it, “upon reuniting the empire in 324 CE [Constantine] built his new capital [at Byzantium]”. Old Rome was no longer on the table – it had become decaying and hard to defend – and Constantine wanted something fresh, something closer to the rich eastern provinces. Imagine him poring over a map of the empire, circling options: “We’ve got Nicomedia and Antioch, or this little Greek town Byzantium down by the straits… hmmm.”

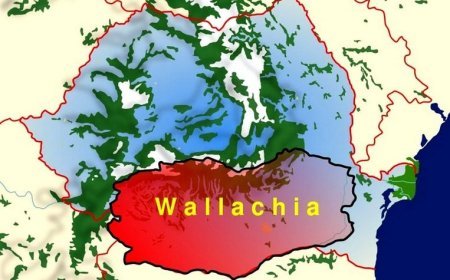

Some plans fizzled out (he even joked that Serdica – today’s Sofia – was “his Rome” for a while). But in the end Byzantium won the prize. Why? In Constantine’s mind it was perfectly placed: it sat almost surrounded by water (so it was easily defended once they strung a heavy chain across the Golden Horn), and it controlled the great sea route between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. From there he could quickly reach the Danube frontier or march east towards Persia. In short, Byzantium was closer to the empire’s economic and military action than dusty old Rome ever was.

Moreover, this new choice sent a message: by leaving Nicomedia (his father and Diocletian’s old capital) and picking Byzantium, Constantine would break with the tetrarchy system and say “I’m the boss now”. Licinius (his defeated rival) had been based at Nicomedia; now Constantine could declare a clean slate. In fact, after Licinius fell in 324, people proposed that the new eastern capital should “represent the integration of the East into the Roman Empire as a whole” – basically a brand-new seat of learning and power for the Eastern Romans. So Byzantium – already rebuilt to Roman standards by previous emperors like Severus and Caracalla – got a makeover fit for an emperor.

Chapter 3: Building Nova Roma (Rebuilding Byzantium)

Constantine didn’t just slap a “For Caesar” sign on Byzantium and call it a day. Starting around 324 AD, he re-built and expanded Byzantium from top to bottom. Think of it like a giant construction project financed by imperial spoils: he tapped into Licinius’s treasury (the war booty) and even levied a special tax to pay for it. Thousands of workers labored for years to carve the old city into a gleaming new capital.

The city quadrupled in size. New walls and gates were built around the peninsula, and on its highest hills Constantine built palaces (his palace had a famous bronze “Chalke” gate) and grand churches. He laid out broad colonnaded avenues modeled on Rome’s, intersecting at big plazas. In one new forum (think of it as a city square), Constantine erected a 100-foot-tall Porphyry Column. This was his centerpiece – not only because it’s still there today (with metal bands holding it together), but because on top stood a statue of Constantine himself, decked out like Apollo the sun god. (Later eyes peeled: Christians would quip that he was standing on “idols,” but at the time it was a way to connect with Rome’s grand tradition.)

To prove how grand this place was, statues of history’s greatest figures lined the streets: Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Augustus, even the emperors before him. And of course dozens of statues of Constantine himself – some of them even had his face on the sun god Apollo’s body, holding an orb and scepter. In one forum, he put a special pillar topped by a holy relic: a piece of the True Cross (the cross of Jesus) inside a shiny orb at its summit. Under that column’s base were said to be baskets used in the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes, Mary Magdalene’s jar, and even the Palladium (a sacred statue of Athena from Troy) – talk about a grab-bag of holy souvenirs!. (Historians debate how much of this is true and how much is later legend, but the sources all agree he packed the city with symbolic treasures.)

Byzantium’s old Greek acropolis (the hilltop shrines and temples) wasn’t bulldozed out of habit, but new churches went up everywhere. For example, Constantine built the Church of the Holy Apostles on the site of an old temple to Aphrodite – an iron-clad way to turn a pagan spot into a Christian one. The very first church in the city, Hagia Irene, was started by Constantine as well. Yet he didn’t banish pagans all at once: the city even had some pagan temples and festivals for a while, reflecting that he was still easing people into Christianity. (After all, he wore a Christian-looking labarum banner in battle, but legend says he only officially converted on his deathbed – never mind, Constantine was a pragmatist!)

The new Constantinople also had new fun stuff: an expanded Hippodrome (for chariot races), a gigantic hippodromic circus monument, public baths, libraries, a mint, a huge marketplace / stock exchange / courthouse building, and massive cisterns underground to hold water (like the Basilica Cistern, built in 330 to deal with droughts). In all, the city was a 4× larger, shinier version of Byzantium – almost a twin of Rome itself. As one source colorfully notes, Constantine’s builders “decorated [the city] with treasures taken from sites around the Mediterranean”. Imagine shipments of Greek statues from Athens, columns from Asia Minor, spoils from North Africa – Constantinople was meant to look like the greatest hits of the ancient world all in one city.

Chapter 4: The Great Dedication (May 11, 330)

By May of 330 the city was ready for its grand opening. On May 11, 330 CE, Constantine held a huge dedication ceremony – forty days of celebration, in fact. According to the Oxford history, on that day “construction was sufficiently complete for that city to be dedicated” and Constantine took part in a solemn Mass in a new church of St. Irene, dedicating the capital to the Virgin Mary. It must have looked like a mix of a pagan festival and a church service (one contemporary column inscription says there were “a mixture of Christian and pagan ceremonies” at the dedication). Thousands of people showed up in their best togas and tobyis (Roman robes) for prayers, parades, and spectacles.

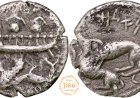

Right in the middle of the celebration Constantine issued a decree with the new name: he declared the city Nova Roma (“New Rome”) as the official new capital of the Empire. This was no surprise – later sources like Britannica confirm that “when Constantine... dedicated the city as his capital, he called it New Rome”. However, the name 'New Rome' didn't have a long life as an official title, and Constantine ordered that the coins be inscribed with 'CONSTANTINOPOLIS' (Greek for 'City of Constantine') in his honor. So by the end of the festivities the place had two big titles: officially New Rome for bragging rights, and Constantinople (Constantine’s City) for daily use.

(Psst – trivia: “New Rome” was mostly a nickname. Historians note the title Nova Roma was never truly official and came down from later on. In practice everyone soon just called it Constantinople, and even coins said that.)

One especially memorable picture from the day: Constantine himself, dressed in imperial finery, standing at the “Milion” (the city’s Zero Mile marker) with a piece of Christ’s cross. And not too far away, his brand-new 50-meter Column of Constantine was erected in the Forum (just think Roman civic center). The emperor’s huge statue on top wore a radiate crown and held a golden ball said to contain a fragment of the True Cross – a heck of a way to claim divine favor. (When the gods of old got the boot, Constantine moved them into shrines or turned them into Christian symbols.)

After all the speeches and prayers, Constantinople was officially on the map. The dedication day lasted forty days according to church records – enough time to watch chariot races, play dice, and feast on roast boar. That feast marked the birth of a brand-new capital.

Chapter 5: Why “New Rome,” Anyway?

Calling the city “New Rome” was packed with meaning. For the Romans (and Byzantines!) Rome was still Rome – the old Western capital – but now their leader was saying “Hey! It’s been moved. We’ve got a second Rome!”. The name Nova Roma was like a medieval king naming a city “Eldorado” (golden city) – it made you sit up. It told everyone: “This isn’t just some provincial backwater; this is the spiritual heir to Rome, but reborn in the East.” As the collector’s magazine notes, Constantine “shook the world of Late Antiquity by moving its center… from the Old to the New Rome”.

This was a big publicity stunt of empire-building. The new Byzantium had all the trappings of the old imperial city: seven hills, grand forums, monuments, and Senate houses (Constantine re-founded a Senate in the city). In fact, there’s an old joke that Greek merchants would say “We’re going into the City” (polis), meaning Constantinople – the same way Athenians say “the City” for Athens. “Is it the same Rome, or a new one?” people would ask – and the answer was, sort of both. One modern writer quips that later Byzantines still called their capital “Second Rome,” and even the church leader’s title includes the phrase Nova Roma to this day.

(For example, today the Patriarch of Constantinople has the title “Archbishop of Constantinople-New Rome” to underline that legacy. The name Istanbul would come much later, but in its heyday the city was very much the Empire’s Rome № 2.)

Religiously, “New Rome” hinted at a Christian rebirth of the empire. Constantine had already legalized Christianity (Edict of Milan, 313 AD) and he celebrated the dedication of Constantinople with a Mass for the Virgin Mary. Orthodox tradition says the city was put under her protection right at the start. So it wasn’t just a political capital: it was meant to be a spiritual capital too, the headquarters of Christendom in the East. In constantinople you’d find a fusion of Christian and classical symbols. For example, coins and statues mixed Christian imagery with echoes of the old gods: a coin from Constantine’s time shows him crowned by Tyche (the personification of the city’s fortune) – literally Rome’s goddess being replaced by a city-run-sort-of-goddess.

Symbolism abounded. Constantine famously had a vision (or, let’s say, a “hunch”) that led him there. Later lore claims an angel guided his spear around the city’s edges as he laid it out. (These stories are charming but not first-hand evidence, more like mythology dressed up as history.) They were meant to show divine favor: God Himself wanted New Rome built. And indeed, Constantine lined the city with relics for good measure. The Milion was crowned with a piece of the True Cross, and underneath the Column of Constantine was reputed to lie a treasure of holy items – making Constantinople perhaps the most “blessed” big city in Christendom.

Political theory also played a part: by elevating Byzantium, Constantine was balancing the empire. The East was richer and more urbanized than the West, so putting the emperor’s seat there reflected the empire’s new reality. One history notes that after Licinius (a Greek-pagan emperor) fell, “it was proposed that a new eastern capital should represent the integration of the East into the Roman Empire as a whole”. In other words, Constantinople was meant to unite Greek-speaking lands with Rome’s Latin legacy. Constantine’s city had to be great: four times as big as old Byzantium, and fit to last a thousand years (spoiler: it did!).

In short, “New Rome” was Constantine’s sales pitch: an all-star successor to ancient Rome, part political capital, part Christian Jerusalem. He even quipped through coins and titles that it was the second coming of the Eternal City. Everyone in the Eastern Empire called themselves Romans (Romaioi) as if nothing had changed – only their emperor had a new address.

Chapter 6: Facts vs. Legends – What Really Happened

When histories and legends swirl together, it’s worth sorting them out. Fact: We know for sure that on May 11, 330 AD, Constantine formally dedicated the rebuilt Byzantium as the new capital and declared it “New Rome”. We have contemporary coins and writings to prove the date and the name change. Fact: Archaeology shows massive building projects in the 320s – new walls, churches, forums – and sources mention Constantine dedicating churches and forums (for example, he built a church of the Holy Apostles on the site of an Aphrodite temple). Ancient chroniclers of the time record many of these moves (Constantine’s edict, the Senate in Constantinople, etc.). These are solid history.

Then there are the legends and theories. Later Byzantine writers tell us amusing stories: one says Constantine traced a boundary with his spear until he felt divinely guided to stop. Another claims an unseen angel marched in front of him as he laid out the walls. These make great paintings and icons (and the Orthodox tradition certainly loves them). However, historians note that these accounts appear generations later and are more devotional than documentary. They might reflect Constantine’s piety, but we can’t take the spear-and-angel tales as literal history.

Scholars also debate why exactly he did it. Some theories (backed by the location’s clear advantages) say it was military and economic logic: a defensible harbor, control of trade routes, and proximity to the turbulent frontiers. Others note political reasons: distancing the throne from Rome’s old aristocracy, absorbing the East into one system, or even trying out an absolute empire under one emperor (rather than sharing power as under Diocletian). Orthodox writers emphasize the religious angle: Constantine wanted a thoroughly Christian capital, away from Rome’s pagan traditions.

While each motive is plausible, historians tend to agree it was a mix of all these factors. The New Rome was part strategic stronghold, part personal legacy project, and part holy symbol. What’s certain is that on that day in 330, Constantine broke ground on a new era. The facts — the founding, the dedication, the name-change — are set in stone (and on coins). Legends about visions or magical foundations can be fun, but they’re the cherry on top of a very real historical sundae.

Chapter 7: The New City’s Legacy

In the end, Constantine’s gamble paid off. Byzantium-turned-Constantinople stayed the Roman Empire’s capital for the next thousand years. Under it came to be known as the Byzantine Empire (we moderns use that word, though the people called it the Roman Empire). Constantinople would outlive old Rome by centuries, standing as the jewel of Eastern Christianity and Greek learning. All of it traces back to that spring day in 330 when Constantine threw open the gates and declared “New Rome” to the world.

So next time you stroll through Istanbul’s ancient walls (Istanbul is the name the city got in the 20th century), remember: it was here that an emperor mixed politics, piety, and plain old “wow” into a city that was supposed to outshine old Rome. And in many ways, it did. Constantine built more than a city – he built a symbol that an old empire could, in fact, become new again.

Sources: This story of 330 AD comes from ancient historians and modern scholars alike. (Notably, ancient coin inscriptions and later chronicles give the dates and names.) Archaeologists and Byzantinists today piece together the details from the ruins, while historians like Mango, Norwich, and others have written down the why and how. Wherever possible we’ve stuck to what the evidence shows (and we’ve flagged legends when they show up). All the highlighted facts above are backed by reputable sources: for example, Britannica and the World History Encyclopedia provide the backbone of these events. But most importantly, the city built on May 11, 330 lives on in our history books – as Constantinople, the New Rome.

Citations:

- Istanbul | History, Population, Map, & Facts | Britannica

- Byzantium - Wikipedia

- Constantinople - World History Encyclopedia

- Constantine the Great - Wikipedia

- Constantine dedicates Constantinople | OUPblog

- Column of Constantine - Wikipedia

- Commemoration of the Founding of Constantinople - Orthodox Church in America

- Christianity and the Late Roman Empire | World Civilizations I (HIS101) – Biel

- New Rome - Wikipedia

- 7 Reasons Why Constantinople Was So Important | TheCollector

What's Your Reaction?

Like

1

Like

1

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0