17 May 1395 – How Wallachia Defied the Ottoman Empire: The Forgotten Battle of Rovine

Discover the dramatic story of the Battle of Rovine, fought on May 17, 1395, where Mircea the Elder’s Wallachia defied the mighty Ottoman Empire. This richly illustrated, accessible project blends history, legend, and strategy to revive one of Europe’s most overlooked turning points.

The Mud-Splattered Clash at Rovine (May 17, 1395)

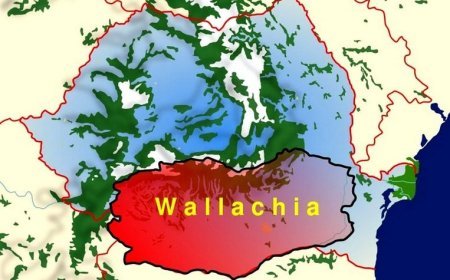

In 1395, a small forest in the Balkans became the stage for one of medieval Romania’s most famous fights. Wallachia was the land ruled by Voivode Mircea the Elder – a shrewd leader who liked to say (in true Latin style) “Fortes fortuna adiuvat” (“Fortune favors the brave”). Opposing him was Sultan Bayezid I “Yıldırım” (the Thunderbolt) of the Ottoman Empire. Bayezid’s nickname meant “Lightning” in Turkish – an ironic contrast to what really happened! In fact, the Battle of Rovine pitted Mircea’s few thousand Wallachian peasants and city troops against Bayezid’s vast Ottoman army on May 17, 1395. The Wallachians had the home-ground advantage: Rovine was a swampy forest. It’s said that Mircea once told Bayezid (when disguised as an envoy) “Take your leave peacefully or get splattered in mud” – and Bayezid chose the mud.

The Combatants: Who’s Who of the Mud Pit

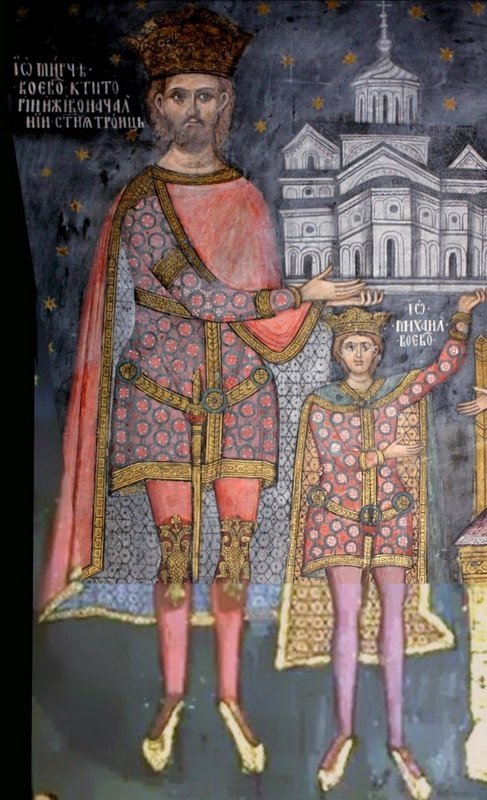

- Mircea the Elder (Mircea cel Bătrân): A seasoned 60-year-old Wallachian prince who styled himself “the great ruler and lord of God’s mercy”. He was broad-shouldered and wise, and proud of Wallachia’s independence. Legend says he even attended the battle disguised as an old peasant or monk to spy on Bayezid’s camp (children’s tale: he carried a loaf of stinky cheese to throw Bayezid off!). Mircea’s troops were farmers and huntsmen, but he also had light cavalry and, crucially, lots of archers hiding in the woods. (Think of them like 14th-century sharpshooters – “bracketing” the enemy with volleys of arrows!)

- Bayezid I “Yıldırım” (the Thunderbolt): A fiery Ottoman sultan fresh from victories in Greece and the Balkans. He brought maybe 40,000 men – cavalry in shining armor and the fearsome Janissary infantry guards. Bayezid was confident he’d batter Wallachia quickly. He expected to sweep through – hence “Thunderbolt”! But when armies met in marshy Rovine, Bayezid’s big horses slurped and sunk, and even he couldn’t crack Mircea’s ambush.

- Bayezid’s Allies: The Sultan’s entourage included some famous knights: Stefan Lazarević, the Serbian despot (another Ottoman vassal) and Marko Mrnjavčević (Prince Marko of old Serbian legend). Both fought with Bayezid under the assumption “Let's crush these heretics!” but fate had other plans. Stefan survived with honor, but Marko was cut down in the swamp – later stories remember that great hero “died fighting at Rovine”. (Eminescu poetically called him a “sons of kings” who fell heroically.) Also on Bayezid’s side was Constantine Dragaš (a Serbian magnate), who also perished. In other words: Bayezid brought a royal collection to Rovine, and it all got ruined by the mud.

Legend of the White Flag: Parley and Pride

The night before the fight, legend says Mircea “played messenger” to Bayezid – but not as a coward. Dressed as a simple monk or envoy, he bravely approached the great sultan’s tent and famously (though quietly) offered Bayezid safe passage if he simply left Wallachia in peace. Imagine Bayezid’s face – a hulking warrior outraged to be questioned by an old man! Bayezid tossed back an imperial reply, roughly: “Wallachia is now Ottoman soil – kneel or die!” Of course Mircea refused (“Per Terram Nostram!” – “Not on our land!”) and stormed off. It was Bayezid’s choice to fight, and Mircea’s to resist. A famous story even says Mircea then “somehow shot so many arrows that they darkened the sun” – a poetic image echoed by chroniclers, though not literally true.

This daring parley is probably more folklore than strict history, but it set the mood. Mircea had shown galantries (acts of courage) and a twinkle in his eye, while Bayezid, stubborn as a mule, was compelled to put on armor by dawn. (Mircea was basically saying “Prince, get out of our back yard!” – an insult straight to a sultan’s ego.) In Latin terms one might say Bayezid gave Mircea “panem et circenses” (bread and circus) – except Mircea wasn’t impressed by empty promises. Instead, Rovine would be more like “bellum et pluvias” (“war and rain” – since the battle took place under a drizzly sky on soggy ground).

The Fighting: Mud, Arrows and Cavalry

When the battle kicked off, it was mayhem. Bayezid formed his knights for a direct charge – but those horses hated mud. Turkish and Serbian heavy cavalry plunged into Rovine’s bog. Meanwhile Mircea’s troops hid behind trees and rocks. The Wallachian archers loosed volley after volley into the enemy ranks, severely thinning them before they even closed in. Imagine tens of arrows whistling like angry bees – even Bayezid’s fine armor wasn’t bulletproof!

As the Ottomans slogged forward, Mircea sent light horsemen to flank them. The enemy vassal knights (Lazarević and Marko) did charge bravely. In fact, Stefan Lazarević fought like a dragon (history calls him “great courage,” nobly covering Bayezid’s retreat), but his cousin Marko was not so lucky – he and his brother Andreja were slain in the fray. (Funny note: Serbian folk songs later made Marko a drinking buddy of the hero Philiop – but there was no drinking here, only blood and mud.) One chronicler says Mircea had only about 10,000 men vs Bayezid’s 40,000, so he relied on terrain and surprise, not open clash. In medieval jargon, Mircea chose a “cauldron-fight” – fighting in a pot of mud and forests – to neutralize the enemy’s numbers.

By the end of the day, both sides were battered. Many Ottoman cavalry horses were bleeding or exhausted, and the janissaries (the Sultan’s elite infantry) held a central position that the Wallachians couldn’t break. The battle “lasted not just one day but a week” in some accounts – really a war of attrition. Eventually Mircea realized “we’ve spilled enough sweat and blood” (Latin phrase: sanguine nostro satis effuso), and ordered a retreat toward Transylvania. Bayezid, too, was exhausted. Neither army got a clear knockout. In tactical terms, Bayezid’s front line (protected by Janissaries) held, but Mircea’s people had pushed the invaders out of Wallachian territory for the moment. In short, each army withdrew, both claiming a sort-of victory.

Mircea’s victory (as his people told it) was truly heroic – he had “thrown the Ottomans out of the country”, even though it was tough and won by a whisker. Bayezid’s chroniclers grudgingly admit Wallachia “held the battlefield,” an honor very few at that time could claim against the Sultan. In fact, a later Christian crusade at Nicopolis (1396) would try to repeat a similar stratagem (catch Ottomans in place), but as one Ottoman veteran of Rovine noted, “The Serdar’s camp was too strong to break!” mirroring Nicopolis.

Aftermath: Winners, Losers, and a Throne Change

Both sides limped away with heavy losses. Bayezid’s broken banner still flew over the battlefield, but the Wallachians saw themselves as heroes of defense. Mircea marched north to Hungary, allying with King Sigismund. Together they even recaptured a fortress called “Little Nicopolis” (Turnu) on the Danube. However, politically Wallachia soon hit trouble: back home, Vlad the Usurper (Vlad Uzurpatorul) seized the throne while Mircea was away. Sources aren’t clear if Bayezid helped install Vlad, or if Vlad simply took advantage. Some say Mircea was forced to pay tribute (a “cover-my-swirling-deeds fee” in Bosphorus-speak) to avoid another invasion, but he basically lost two fingers as price for his bravery.

In Europe, Mircea’s stand became famous. Westerners knew only that “the Vlach voivode resisted the Sultan”, and it helped inspire later Crusades. In fact, Emperor Sigismund invited Mircea to the big Christian conference – even though Nicopolis (next year, 1396) would fail disastrously. Historians now wonder: what if Mircea had joined Nicopolis’s knights? Would Rovine have changed destiny? We don’t know, but for Romanians Battle of Rovine is like Little Security Council – proof Wallachia once said “Not so fast, East!”.

Scrisoarea a III-a: Poetry Meets History

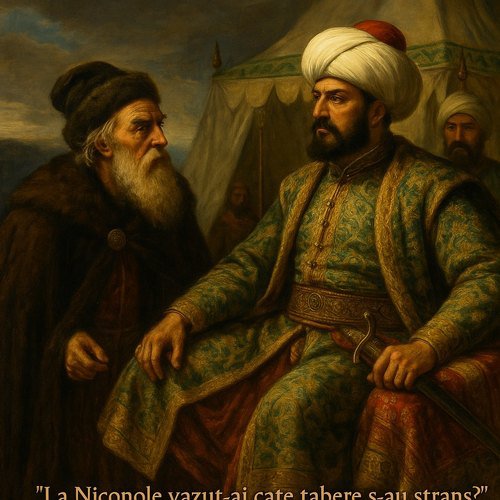

Centuries later, the great Romanian poet Mihai Eminescu immortalized Rovine in his epic poem “Scrisoarea a III-a” (“The Third Epistle”). He wrote it in 1871 as a letter from Mircea to Bayezid. It’s fiery and dramatic: Mircea is transformed into a wrinkled, fiery old hero who hurls insults (with funny rhymes) and warns the Sultan of Christian vengeance. Eminescu even lets Mircea mention “Nicopole” as if he had won a great victory there, and muses about future Christian kings on the throne of Rome – a patriotic daydream. (In reality Bayezid won Nicopolis and Constantinople stood for decades, but Eminescu used poetic license.)

In Scrisoarea III, Mircea and Bayezid trade barbs like rival cartoon characters. Eminescu paints Bayezid’s camp lavishly with eastern trappings, then has Mircea grumble about Ottoman arrogance. For example, Mircea’s voice says: “La Nicopole văzut-ai câte tabere s-au strâns” (“At Nicopolis, have you seen how many armies gathered”)? – implying Bayezid’s defeat, when actually it was a Christian defeat. Historians note this is “fictionarii” – Eminescu fudged events to make Mircea seem all-powerful. But it worked: Romanian schoolkids learn Mircea’s defiant “We welcome the foreigner only in our grave!” lines with awe. In short, Scrisoarea III is part myth, part history – it captures the spirit if not the timeline. It inspired national pride, so we explain it here: Bayezid demanded Mircea kneel, Mircea (in comic-stern old-hero style) said “Nay, by the Fatherland!”, and epic rhyming warfare ensued.

Broad Ripples: Rovine’s Echoes in Europe

What did this scrappy battle mean beyond the mud? Surprisingly, quite a bit:

- Inspirational example: Mircea’s defiance showed Christian Europe that the Ottomans could be stopped. At least briefly. For Eastern Europe (Hungary, Poland, even distant papal advisers), Wallachia was a “back door” to the Ottoman lands. Mircea’s guerrilla tactics later influenced how Byzantines and Hungarians fought. (The Ottomans themselves learned a lesson: “never again get stuck in a swamp”! – they built pontoon bridges better next time.)

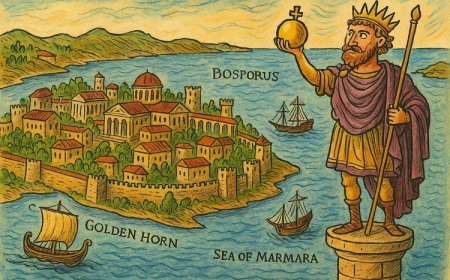

- Connection to Dacia and Rome: Rovine fed into the story that Romanians were heirs of ancient defenders. If Mircea was a modern-day Trajan, then Wallachia stood on old Roman soil. As poet Vasile Alecsandri quipped, Mircea “protected the bridges of Vienna” against the Turks, echoing Roman imagery. This battle thus became symbolically linked in national memory to the days of Decebal (Dacian king) and Trajan – a medieval echo of the Roman wars.

- On a World Stage: Even far-off nations note May 17th in history. Curious coincidences: on May 17, 1742, exactly 347 years later, another swampy encounter occurred in Europe – the Battle of Chotusitz in Bohemia. There, Frederick the Great’s Prussian army clashed with Austria. Like Rovine, it was muddy and inconclusive (though Frederick claimed the win). Both battles show springtime can still mean war, not just flowers and picnics.And on May 17 in our own time, other “battles” were waged: in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court Brown v. Board verdict ended segregation in schools – a victory for freedom. We can draw a whimsical comparison: Wallachia’s stand in 1395 was about one people’s independence; Brown v. Board was about racial equality. In both cases, a David showed that an entrenched Goliath could be challenged. So every May 17th, history reminds us some brave souls fought for liberty – be it against swords or prejudice. (And in 1990, the WHO erased homosexuality from its list of illnesses – another kind of battle won on May 17.)In short: history has a sense of humor. If Bayezid had returned for revenge exactly one human lifetime later, he would have landed on the eve of the Kentucky Derby’s founding (1875)! Napoleon’s armies were busy elsewhere on May 17, 1805 (in Italy), and on May 17, 2019 modern cruise missiles rained in the Middle East. But the spirit of resistance – the heart of Rovine – endures in any fight for freedom.

Trivia and Tidbits

- “Rovine” means “ruins” in old Wallachian. Some say the battle took place near ruined fortresses – perhaps inspiring the name. Others think it refers to the “ruined” dead bodies after. Either way, it’s a catchy (if gloomy) name that Romanian schoolkids remember.

- Latin quotes: Medieval documents often called Mircea “Io Mircea, great Voivode” and used Latin everywhere. One Latin motto from the era goes “Aut Caesar aut nullus” (“Either Caesar or nobody!”) – capturing Bayezid’s attitude (ruthless ambition). Mircea might as well have answered “Sed castra mea non est vestra, inimice!” (“But my camp is not yours, enemy!”) if he spoke Latin – an attitude clear in Scrisoarea.

- Comic analogies: Think of Rovine as the medieval Battle of the Bulge: armies clogged in bad terrain. Or like a game of Risk gone awry, with one player hitting “auto-win” but slipping on a banana peel. Bayezid had his huge cavalry pieces lined up, but Mircea turned the map over and pounced with guerrilla moves – a surprise “Revenge of the Wallachian!”

- What ifs: If you like alternate history, consider: if Mircea had fallen instead, would Wallachia have become an Ottoman province? Would Vlad the Impaler’s father, Radu the Handsome, have grown up under a different throne? These are the deep “History mysteries” that pulp novels live on.

Sources and Further Reading

For those interested in exploring the Battle of Rovine in more depth, a variety of resources shed light on this pivotal event in Wallachian and Ottoman history.

- General Historical Overviews: Encyclopedias like Britannica and Wikipedia provide solid summaries of the battle, generally describing Mircea the Elder’s victory over Bayezid I on May 17, 1395.

- Medieval Chronicles: Traditional Romanian and Serbian sources—such as the Dečani Chronicle—offer detailed accounts of the battle and mention the notable deaths of regional figures like Marko and Constantine.

- Modern Scholarship: While the precise date and location remain topics of academic debate, historians agree on the importance of this muddy battlefield as a symbol of heroic resistance. Recent articles and university publications provide thorough analyses (e.g., Balcanica Posnaniensia).

- Cultural Perspectives: Romanian national poet Mihai Eminescu’s “Scrisoarea a III-a” poetically memorializes the battle. Look for editions with scholarly commentary to separate history from legend.

- Broader Context: Understanding the battle also benefits from reading about the Ottoman–Hungarian wars and the reign of Sigismund, who played a role in the aftermath. Additionally, studies on medieval Romanian identity connect Rovine’s legacy to ancient Dacian and Roman roots.

For an accessible starting point, online entries and summaries serve well, but for serious readers, works by historians such as Fine, Angell, Bradbury, and Czamańska provide detailed perspectives on the subject.

Citations:

- Battle of Rovine - Wikipedia

- Wallachia - Wikipedia

- Origin of the Romanians - Wikipedia

- Mircea the Elder - Wikipedia

- Marko Kraljević | Ottoman Wars, Battle of Kosovo & Serbian Hero | Britannica

- A few observations on the battle of Rovine (1395) | Balcanica Posnaniensia. Acta et studia

- Cât de mult a greșit Eminescu? - Contributors

- Battle of Chotusitz - Wikipedia

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0