📜 16/28 May 1812 — The Pact That Redefined Eastern Europe

Explore the Pact of Bucharest (1812), a pivotal treaty that reshaped Eastern European borders and identities. This comprehensive guide delves into the historical, political, and cultural impact of the treaty, revealing forgotten connections and awakening the legacy that still influences nations today. Accessible to all ages, this educational resource combines accuracy with engaging storytelling to bring history to life.

The Pact of Bucharest (1812): Borders Redrawn, Histories Intertwined

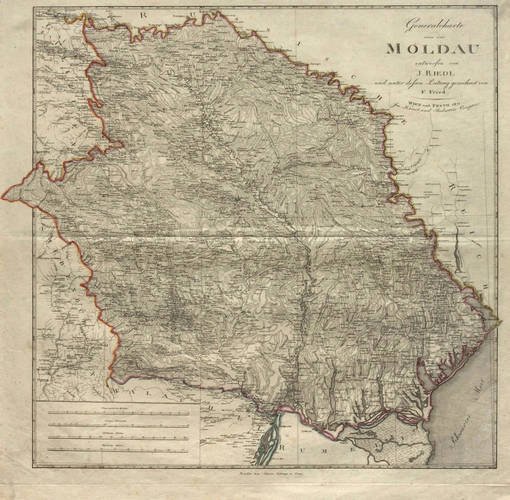

The Principality of Moldavia before the Treaty of Bucharest (1811)

The Principality of Moldavia before the Treaty of Bucharest (1811)

by J. Riedl, under the supervision of F. Fried. Vienna and Pest, 1811

How the Treaty Shaped Nations, Identities, and a Century of Change

Chapter 1: The Road to War and the Shattering of the Principalities

By the early 1800s, Europe was a giant pressure cooker. The Russian Empire under Tsar Alexander I eyed the weakling Ottoman Empire to its southwest, while the Napoleonic Wars raged across the continent. Sultan Selim III (and later Mahmud II) in Constantinople was entangled in this great-power tug‑of‑war. Russia wanted to secure its southern flank before Napoleon’s invasion (and did not relish a war on two fronts). Meanwhile, France egged the Ottomans on to oust pro-Russian princes from Wallachia and Moldavia (the Danubian Principalities), sparking conflict. The result? In late 1806 the Russians flooded across the Danube and Dniester rivers, seizing Hotin, Bender, Chilia, Ismail and more. By November, all of Moldavia and Wallachia were under Russian control. (Cool visual: imagine a blond bear marching over a map of Eastern Europe!)

Chapter 2: Who’s Who in 1812

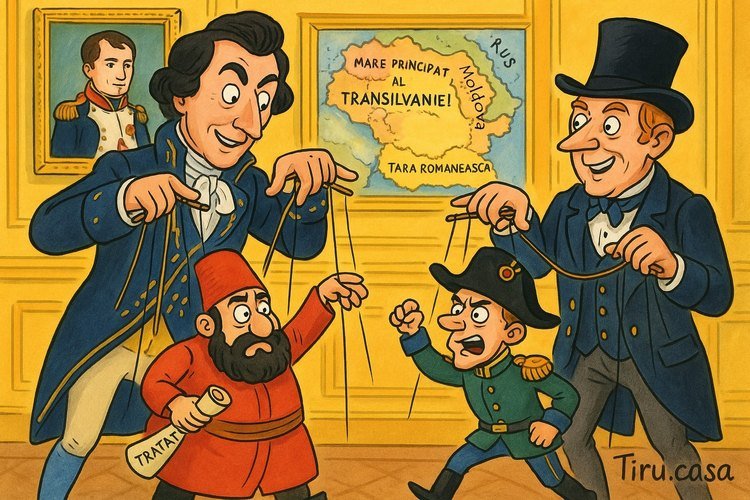

The deal involved some big personalities. Tsar Alexander I of Russia was the nervous hero here: he secretly wanted both Principalities but officially claimed only to guard against Napoleon. On the Ottoman side sat Sultan Mahmud II (ruling since 1808), who was juggling foreign meddling (Britain and France encouraged him to resist Russia) and domestic unrest. A colorful local hero was Emanuel (Manuc) Bei, an Armenian merchant whose famous inn in Bucharest would host the peace talks. In the Principalities themselves, rulers came and went like fashion trends. In 1806, Sultan Selim (on French advice) deposed Wallachia’s prince, Constantin Ypsilanti, for being “too friendly” with Russia, replacing him with Alexander Suțu. The same happened in Moldavia, swapping out Alexandru Moruzi for Scarlat Callimachi. These princes played cat’s-paw between empires.

Behind closed doors sat the negotiators: Russians sent generals like Jean Sabaniev and Francophones like Joseph and Antoine Fonton (because French was la langue diplomatique). The Ottomans fielded their own Reis Efendi and Mufti effendis in velvety robes. Even Britain and France played puppetmaster: as one historian quips, British and French mediators dragged out the talks not out of love for the Sultan, but to “limit Ottoman losses” and slow Russian expansion.

Chapter 3: Battles, Armies and Ambushes

From 1806 to 1811, battles raged across the Balkans and even the Caucasus (behind all this, there were wars with Persia and in Georgia, but that’s a sidebar). The Turks tried several offensives in the Principalities, but flopped: at Obilești (14 June 1807) and Malainița (19 June 1807) they were soundly beaten. The Russians even won sea victories in the Aegean, and at Arpachai (in Armenia) where a few thousand Russians routed 20,000 Ottomans. After another Russo-Ottoman ceasefire in 1807, peace was no more. By 1811, both sides were exhausted but ready to negotiate – Russia because Napoleon’s Grand Army was at her doorstep, and Turkey because her coffers were empty.

At Giurgiu on the Danube (Nov 1811), Russian and Ottoman envoys first sat down. The Russians started modestly (Prut border), then tried to supersize to the Danube itself (meaning all of the Romanian lands) – even pointing out that Napoleon had given his blessing at Erfurt. The Sultan balked, wanting to keep the Danube mouths (forts at Ismail and Chilia). So the Russians upped the ante: they resumed fighting. In one ambush, retreating Turkish troops were lured into a trap and surrounded. Knowing his empire was in danger, Sultan Mahmud II finally relented.

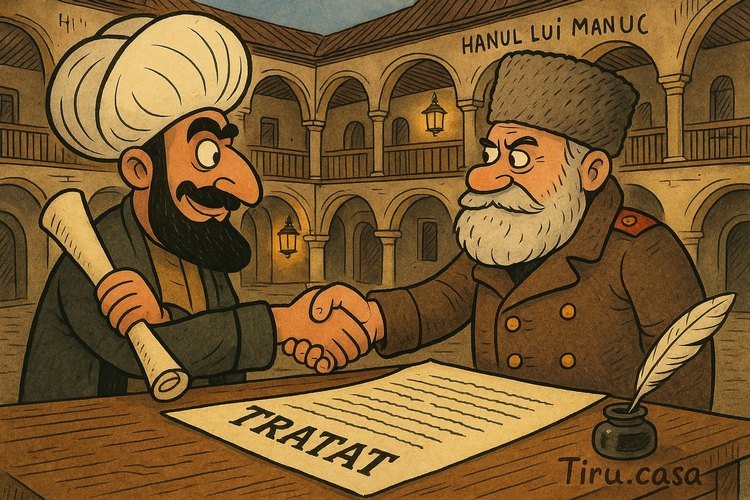

Chapter 4: The Signing at Manuc’s Inn

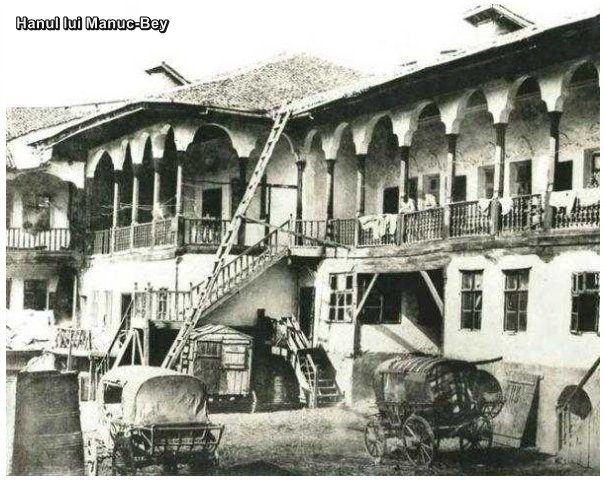

By May 1812, the Ottoman Grand Vizier and Russian generals met in Bucharest. The great Manuc’s Inn (Hanul lui Manuc) – a vast 1808 courtyard inn – became the negotiation hall. (Imagery: think of a candle-lit innroom with long tables and secretive talk.) On May 16/28, 1812 (Julian/Gregorian calendar), Tsar Kutuzov’s envoy and Sultan Mahmud’s plenipotentiary appended their names. The agreement was in effect a capitulation for the Porte: the Ottoman ambassador Khurshid, famously, afterwards took poison rather than face the Tsar.

Manuc’s Inn, depicted by an engraving from 1841 (left) and a photograph from 1867–1870 (right).

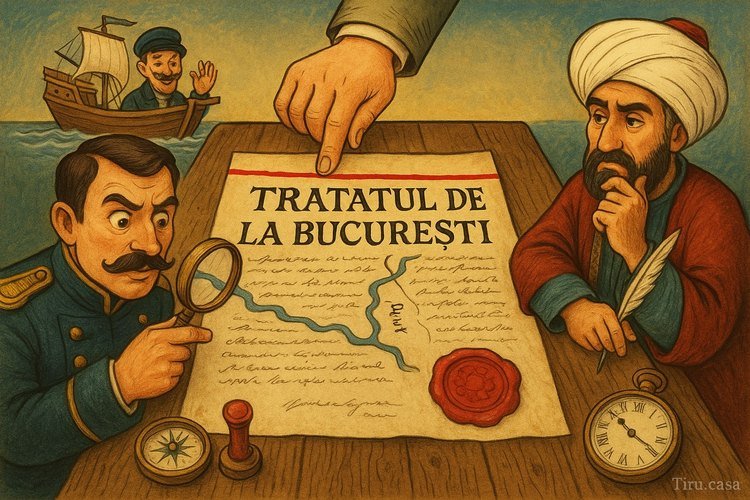

Chapter 5: Treaty Terms – The Fine Print (and Big Print!)

The treaty had 16 articles – a legal roadmap to a new border. Here are the highlights:

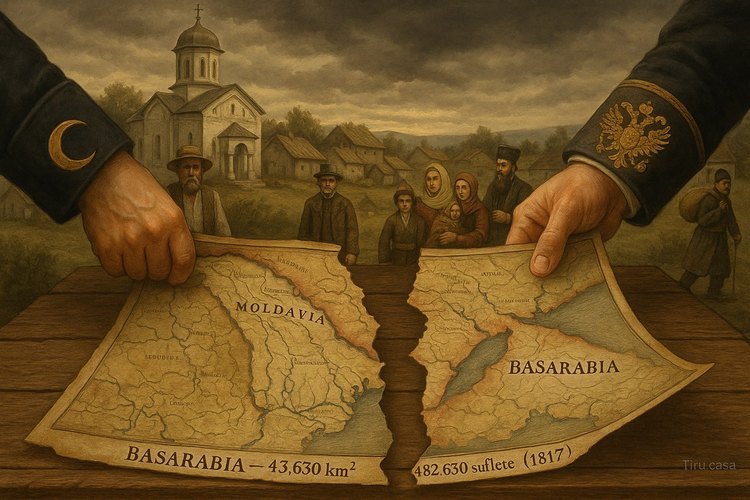

- Article 4 (the Big One): It drew the new border. “The Prut river… and from there the left bank of the Danube… to the Chilia mouth” would be Russia’s frontier. This ceded the entire eastern half of Moldavia (between Prut and Dniester), plus the strategic Budjak region on the Black Sea, to Russia. (That was about 45,630 km² – bigger than pre-1812 Moldavia.)

- Danube Rights: Russia gained special trading privileges on the Lower Danube. (Imagine a merchant captain winking at officers as he sails freely upriver – thanks to this treaty!)

- Articles 1–3, 5–6: Diplomatic niceties like mutual goodwill, amnesties, honoring previous treaties, and tax rules. Peasants were allowed four months to move if they found themselves in the “wrong” country.

- Article 7: Gave 18 months for any Muslims or Christians to emigrate across the new border if they wished. They could sell their farms and take their money with them (the Ottomans even promised to help Budjak Tatar refugees with travel expenses).

- Article 8 (Serbia): Although a bit of a side-story, it guaranteed the rebellious Serbs something like semi-independence. Ottoman forts in Serbia were to be razed – a small bonus for the Russians (and Serbs) at Istanbul’s expense.

Chapter 6: The New Map – Geography and Demography

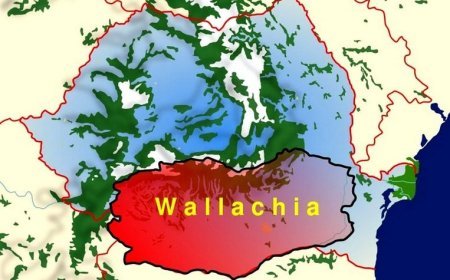

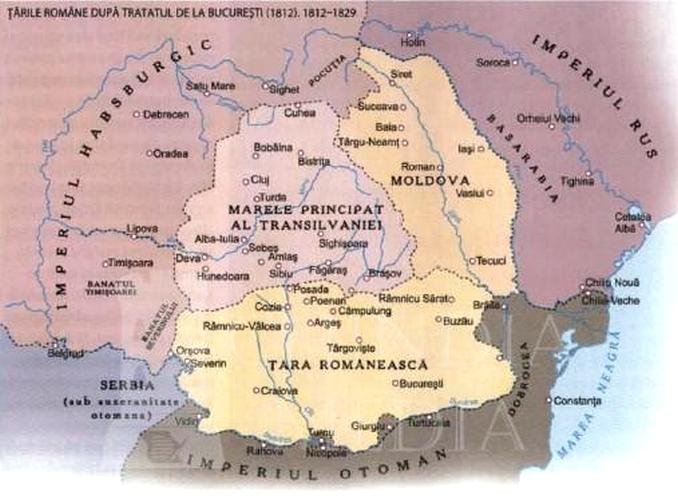

The map of Romania changed dramatically overnight. The Prut River became the new western frontier of Tsarist Empire. The old Principality of Moldavia was snapped in two: the west (Moldavia) remained under Ottoman suzerainty (soon re-administered as part of Wallachia), while the east became Russian Bessarabia. Russia now held roughly 43,630 km² and 482,630 souls – five forts, 17 towns and 685 villages. (That population was almost entirely rural and Orthodox; a few Tatar and Jewish communities lived there too.) In fact, the rest of Europe started calling the eastern chunk “Bessarabia” as if it were a new country.

- Maps & Stats: The new Bessarabia Governorate (1818) included modern Moldova and parts of southwestern Ukraine. It grew quickly: by 1817 it had ~482,000 people. Over the next decades, Tsarist Russia invited settlers: German colonists, Bulgarians (in the south), and Gagauz Turks arrived, while many Tatars left for Ottoman lands.

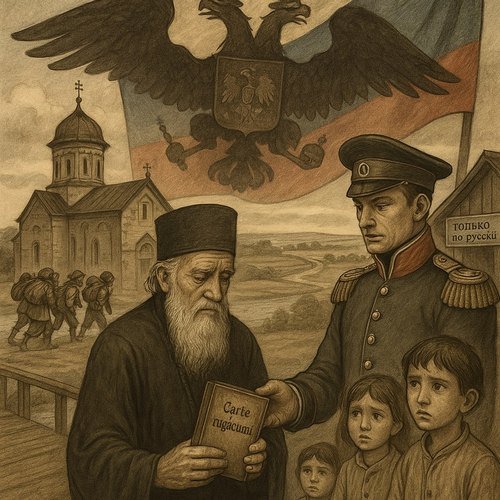

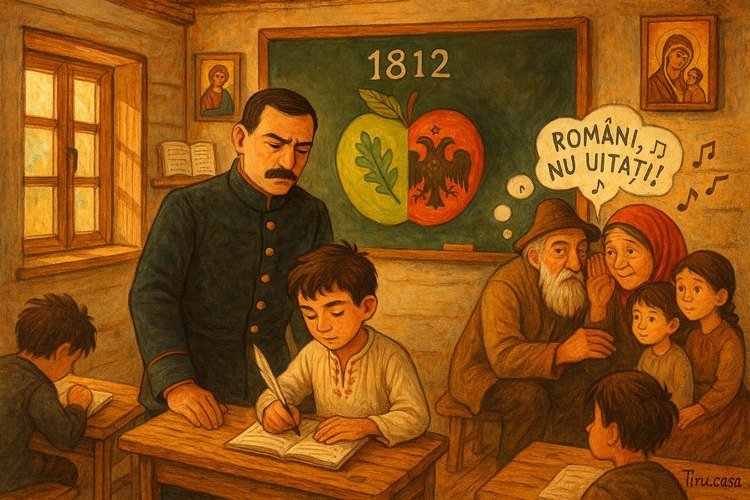

- Language and Faith: Most locals spoke Romanian (Moldavian dialect) or Bulgarian, and were Orthodox Christians. (Soviet-era maps often ignored Romania’s historical tie to Bessarabia, but local memories kept it alive.)

This re-drawing of borders was a geopolitical earthquake for Romanians. Suddenly, a large chunk of their old homeland was under foreign rule.

The Romanian Principalities after the Treaty of Bucharest (1812). 1812-1829

Chapter 7: Life Under the Russian Eagle

What happened to the people of Bessarabia? The Tsar’s government re-organized the territory as an oblast (1818) and later a guberniya. Initially, Alexander I even granted it a degree of self-rule: he installed a Romanian-speaking governor and church officials, and promised to respect Orthodox customs. But the 19th century took a hard turn toward Russification. By 1834, Romanian (“Moldavian”) was banned from schools and churches, according to Bessarabian emissary Vasile Stoica – with anyone caught rebelling risking exile to Siberia. In effect, the old Principality was dissolved: Russian became the language of government, and Orthodox clergy came under St. Petersburg’s thumb.

Life was a mix of new roads and farms and heavy taxes. Some locals welcomed the Tsar’s peace and investment (the land was fertile), while others grumbled about losing their princes and traditions. Many Bessarabians actually left: around 30,000 peasants emigrated west of the Prut to avoid Russian rule. Over the decades, a unique Bessarabian identity emerged – a blend of Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian, and Turkish influences.

Chapter 8: Legends, Myths and Realities

For generations, the loss of Bessarabia became a founding myth in Romanian culture. Folk songs and tales mourn a stolen land: grandparents might have whispered about Cossacks snatching children, or about the Tsar’s greed. One common story is that Romanians offered Bessarabia to Russia as a buffer – but the truth is messier: it was taken by war, not given freely. Similarly, some myths say “Basarabia always wanted to unite with Romania,” ignoring that many locals had mixed loyalties after a century of Russian rule.

In schools (pre-1989), Romanians often learned that Basarabia was “our lost province, unjustly taken by the Tsar.” That painful narrative isn’t entirely false, but it oversimplifies: remember, Bessarabia was multiethnic and had been under Ottoman suzerainty itself. The real, forgotten truth is that 1812 set in motion a 100‑year experiment: half-Moldavian under Russia, half under the Ottomans (later Ottomans handed Wallachia to the Habsburgs for a bit, etc.). What survived were cultural ties: orthodox churches, the Romanian language (in private), and local rulers like Ioan Sturdza, who actually became Moldavia’s prince in 1812 under Russian patronage.

Chapter 9: Echoes in the 21st Century

The Treaty of Bucharest’s shadow stretches into today. After World War I, Romania and Bessarabia briefly reunited (1918–1940), only for the Soviets to snatch it back in World War II – another traumatic shift. Today, the old border lies between Romania (EU/NATO) and the independent Republic of Moldova (a former Soviet republic whose people largely descend from Bessarabia). The two nations still share language and history, though some Moldovans have a distinct “Moldovan” identity.

Since the 1990s, Romanian presidents and Moldovan leaders have played the “Romanians under one roof” card. In the 2020s, President Klaus Iohannis of Romania and Maia Sandu of Moldova built a personal friendship “to advance European integration under Russia’s shadow”. Romania used its EU membership to push Moldova’s EU bid (starting accession talks in 2024). Meanwhile, Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine put the world’s eye on Bessarabia once more. Suddenly the Ukrainian part of historic Bessarabia (south-west Odessa region) was under attack: resistance there was fierce, and locals repelled Russian raids. This showed how “this strategic borderland” has flipped from pro-Russian to staunchly Ukrainian in a flash.

In short, the Treaty of Bucharest of 1812 is not just a dusty historical footnote: it’s a story of drawing lines on maps and in minds. From witty folk rhymes to serious diplomacy, its legacy lives on. Or as a Latin phrase might go (with some poetic license): Historia magistra vitae est – History is the teacher of life.

Citations:

- Manuc's Inn – Wikipedia

- Bessarabia – Britannica

- Bessarabia – Wikipedia

- Romania and Moldova: Europe’s “Special Relationship” – New Eastern Europe

- After Russia’s Invasion, the People of Bessarabia Switched Sides – The Economist

- How Bessarabia Got Together with Romania – Virtual Museum of the Union (MVU.ro)

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0